Published in Colliers, pp. 22, 23, 71; April 1, 1950

Driver Alphonse Iannicelli hit the siren as soon as the big white ambulance nosed out of the hospital and sped downtown. In the back, Nurse Loretta Partheymuller, her blue beret slapped over her dark curls, checked the address of their destination, a broken-down hotel on New York's Bowery.

As Iannicelli dodged traffic, his hands tensed at the wheel. This was no routine emergency call, but, literally, a race. Minute by minute the balance toward life or death hung on a breath, and a very young breath at that.

When the two hurried into the dim hotel lobby, a white-faced clerk jerked his thumb at a small room and growled:

"But I saw the girl walk past my desk only this morning!"

In the room a twenty-one-year-old blonde lay in bed. Her mother and sister stood by helpless. On a chair, buried inside a towel and dirty bathrobe, was the patient, a prematurely born infant girl, four hours old.

Miraculously, she breathed -- miraculously because every circumstance of her birth had been miscontrived. Brought into the world by two frightened women, she was hardly more than two pounds, a weight at which few premature babies survive. (Medically speaking, a "premature" is any baby born weighing less than five pounds nine ounces.) She was still attached to the placenta by the umbilical cord, which the amateur midwives had not cut. Nor, before help arrived, had they had sense enough to keep her warm and fan the weak spark of life within her.

No baby, of course, is ever a mere statistic, but the fact is that this Bowery child was born into a statistical picture which does no credit to us as a nation. Of an estimated 175,000 premature babies born every year in the United States, about 40,000 die. Premature birth is the greatest single cause of U.S. infant mortality. It ranks eighth among the top 10 causes of death at all ages.

Why do these babies die? Prematurity is not a baffling disease to be fought in the laboratory. They die not because we don't know enough, but because we just don't do enough-in the way of adequate physical equipment and specialized nursing and pediatric care. The tragedy which hits 40,000 American families a year could largely be avoided if we were not so indifferent, neglectful and unwilling to put up the relatively small sum needed for that special equipment and care.

For this particular early baby, the odds on survival were closer to 100 to 1. Yet they were outweighed by one single piece of good fortune. She was born late in 1948, shortly after New York City launched its Premature Transport Service, a 24-hour emergency service using portable incubators, specially designed ambulances with a heating compartment and oxygen supply, and trained nurses whose job it is to move premature babies from their places of birth as quickly as possible to hospitals with specific facilities to care for them.

Essentially, what a premature baby needs is an environment as close as possible to the womb which he has come too soon into this unsterile world. Certain animals, like the kangaroo, regularly give birth prematurely, but the kangaroo has a natural incubator, the pouch. Human prematures also need an incubator, as well as proper amounts of nourishment, oxygen, heat and protection from infection.

Ingenious doctors and nurses have improvised incubators by fitting two cardboard or wooden boxes into each other, and filling the space in between with bags of hot sand or salt or heated bricks and stones. Premature babies have been carried to the hospital on streetcars in market baskets heated by bottles filled with hot water. Some of these babies lived, but a lot of them didn't.

When prematures are born in a hospital, the need for speeding them to another hospital with the special facilities to care for them is not as critical as when they are born at home or, in the case of Nurse Partheymuller's little charge, in neither hospital nor home. A moment's delay may cost a life, and Parthey moved surely and swiftly that cold December morning after she and lanniceIli carried a portable incubator and other equipment into the Bowery hotel.

The tiny infant lay almost exhausted after four hours of struggling just to stay alive, with no help and much hindrance from her grandmother and aunt. They had washed out her delicate eyes with a month-old solution rummaged from the medicine chest. They had poured salt and water into her mouth, already dangerously clogged with mucus. The grandmother proudly admitted that she had once read about such procedures in a book.

Parthey cut the umbilical cord, cleared the throat and nasal passages of mucus by gentle suction with a catheter, dressed the infant in a sterile "premature jacket," a one-piece garment with hood, and snugly berthed her in the preheated incubator, kept warm by four hot-water bottles at the side and bottom. Most important, the baby began at once to receive 4 liters a minute of vital oxvgen from a tank clamped to the incubator's side (two thirds of the premature babies who die are starved for oxygen).

Within minutes, the nurse had finished. Iannicelli carefully carried the portable incubator outside and fitted it into the heated compartment in the ambulance. Parthey switched on the oxygen from the large tanks beneath it.

For Iannicelli the job then really began. A siren isn't quite enough when transporting a barely breathing fragment of humanity. All the way to New York Hospital's premature-baby center, he kept his eyes and head moving to gauge traffic, easing around corners, applying brakes when necessary with a steady smooth pressure, giving every break to his tiny passenger. The ambulance itself was specially built to provide as smooth a ride as possible.

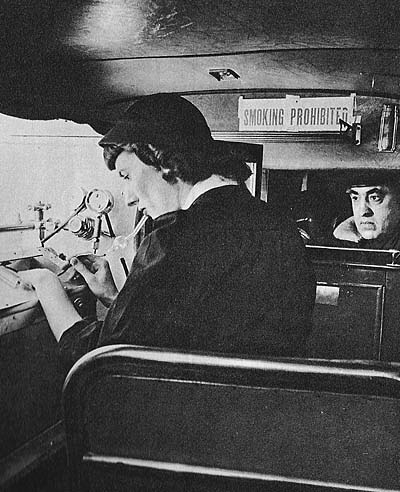

On the way there was a routine for Parthey to follow. Check the oxygen. Watch the temperature. But mostly she kept her eyes on the little form fighting its battle to survive. The amount of energy a premature baby has to spare is small, and it was evident that this baby had spent nearly all of it during those first neglected hours.

To give artificial respiration in a speeding ambulance to an infant hardly bigger than one of your own hands is quite a trick. But Nurse Partheymuller reached into the incubator and with light finger tips massaged the fragile rib cage. Then she gingerly raised the head and feet, bending the slight body like a miniature bellows, to help the baby breathe.

Color returned to the almost transparent skin, and the arms, hardly bigger than one of the nurse's deft fingers, stirred slightly.

Nurse Administers Baptism

Before she closed the incubator again, Nurse Partheymuller took a bottle from her bag. As the ambulance threaded through the columns of the Third Avenue el, she sprinkled a few drops of water on the infant's head.

"I baptize thee in the Name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost," she said in a low but clear voice. In an emergency, nurses are instructed to baptize a Catholic baby who seems to be in danger.

Happily, the Bowery baby became a statistic on the bright side of the tally sheet. She lived. Her surname had been given as "Cornell," and since this baby with all the cards stacked against her became the "star" of the premature center, it was inevitable that the nurses at New York Hospital should give her the rest of an illustrious name. They called her "Katharine."

In all likelihood little "Katharine" would not have survived at all had she been born in any but the handful of U.S. cities which have programs to care for prematures -- Chicago, which pioneered in the field before the war, Detroit, Denver, Baltimore and New York. Although, under the Hill-Burton Act, the federal government offers states and cities technical advice and financial aid -- footing one third of the cost of building and equipping special premature centers -- takers have been few.

Even in those cities which have programs, progress has been agonizingly slow. In New York City alone, for example, approximately 14,000 premature babies are born each year. In its first year the Premature Transport Service picked up a total of 545 babies. And moving them to the proper hospital is just half the problem; the other half is providing the space for them in such hospitals. There are now six New York hospitals with special facilities for prematures, and as yet all of them combined can care for only 58 babies at a time.

Still, what cheers medical authorities is that a start has been made. One of the six New York hospitals, Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, has one of the most modern premature centers in the country. It features new "isolettes," Plexiglas incubators with piped-in oxygen, filtered fresh air, built-in suction equipment and precisely controlled heat and humidity. Through the isolettes the baby can be seen at all times, yet need never be moved or exposed at all until ready to graduate to a heated crib. The nurse attends to the infant's needs by slipping her arms through plastic portholes in the sides. Even the weighing of the baby is done on a sterile sling hanging inside.

There is no truth to the ancient superstition that prematures who survive will always be mentally or physically weak (the Dionne quintuplets and Winston Churchill were prematures). But the need for the best scientific facilities possible is based on the fact that prematures aren't well developed enough to function without help.

Unflagging attention is the key to the care of prematures, and the sooner they begin to get it, the better. More than half of all prematures who die do so during the first 24 hours after they are born, hence the vital importance of speedy transport to hospitals. Baltimore's premature babies travel under the auspices of the fire department. New York's transport service consists of two ambulances. It takes them an average of two hours, from the time the call comes, to pick up and deliver the baby to the hospital.

The ambulances are special affairs whose design was developed in co-operation with one of the big automobile manufacturers by forthright young Dr. Helen Wallace, chief of the Maternity and Newborn Division of New York City's Health Department and head of the Transport Service, and by Margaret Losty, public health nursing consultant. The ambulances boast portable incubators and special heating compartments beneath which are stored large oxygen tanks, and they are constructed to guard against excess vibration.

Four ambulance drivers and five nurses share the 24-hour birth watch of the service, on instant call from their station in the long corridor at Bellevue Hospital, where various city emergency services are located. The drivers, chosen from among the regular city ambulance drivers, alternately refer to the babies as "the brutes" or "the preemies."

Driver Iannicelli grins. "All of my three kids were ten-month babies," he says proudly. "And me driving preemies!"

Because of a Health Department policy of shifting nurses around so that they may get experience in various types of public health nursing, Transport Service nurses serve only a one-year tour of duty. Nurse Partheymuller recently accepted a post as head nurse in the new premature center at Queens General Hospital. But the excitement of her race to and from the Bowery hotel is duplicated regularly by the nurses now on the transport run.

Most of the time the girls take in their stride the odd situations which come their way. Mary Jane Conlon, not long ago, rushed on an emergency call to an apartment where she found a dozen men drinking and playing cards in a smoke-filled room. Nurse Conlon was about to turn on her heel when one of the men motioned to the bedroom. There she found the new mother in bed and alone. In the kitchen a female relative crouched before the open oven door of a coal stove, holding a three-pound infant in her arms and trying to keep it warm and alive; all the while the card game continued in the next room.

Another call was to save a prematurely born gypsy baby. Everyone in this household was also in high spirits, particularly the 35-year-old mother and 17-year-old father. Mary Jane recalls, "We didn't know if we were supposed to help a premature baby or a premature father!"

Nurse Evelyn Nurse was party to one of the most confused, not to say crowded cases in the annals of the service. Six o'clock in the morning is as quiet an hour in Brooklyn as anywhere else, and it was shortly before that when a young woman woke her husband to say that their baby was due soon, almost immediately, in fact.

A Hectic Morn in Brooklyn

He pulled trousers on over pajamas and rushed out to find a telephone. At 6:05 a radio car with two policemen arrived. By 6:15 they had delivered a four-pound baby boy. At 6:17 an ambulance and intern came along. After looking at the mother and boy and congratulating all concerned, the intern muttered, "Just a minute," and delivered a three-and-a-half-pound girl. Shortly after that a sergeant and five patrolmen of the New York Police Emergency Squad appeared with a supply of oxygen. Meanwhile, the father sprinted five blocks to fetch the family priest.

That was the situation when Nurse Nurse and her driver entered to find the mother, father, twins, a doctor, priest and a total of eight policemen in the small flat.

Next to the parents, she says, the widest grin was on the face of one of the two cops who delivered the first baby. He was asked to be godfather to the twins.

Having a premature baby is pretty expensive. The baby must stay in an incubator until it is at least five and a half pounds. The average stay in the hospital is 30 days and costs about $18 a day.

The city and state of New York have proposed a plan whereby they might pay $12 a day toward the care of each premature baby in those premature centers approved by the Department of Health as meeting its proper standards. If the family can pay all or part of the bill, it would be expected to do so.

But the Premature Transport Service itself, as a public health emergency service, is free to all and available simply by telephoning.

At least one citizen wasn't slow to take advantage of the service. One quiet evening, at about ten-thirty, a call came from a highly excited woman. The nurse on duty tried to get details: name, address, how many pounds was the baby?

After some confusion, the woman giggled and confessed:

"Oh my baby isn't due for months and months yet! I just wanted what to do if it should be premature."