Maternité de Paris, Port-Royal

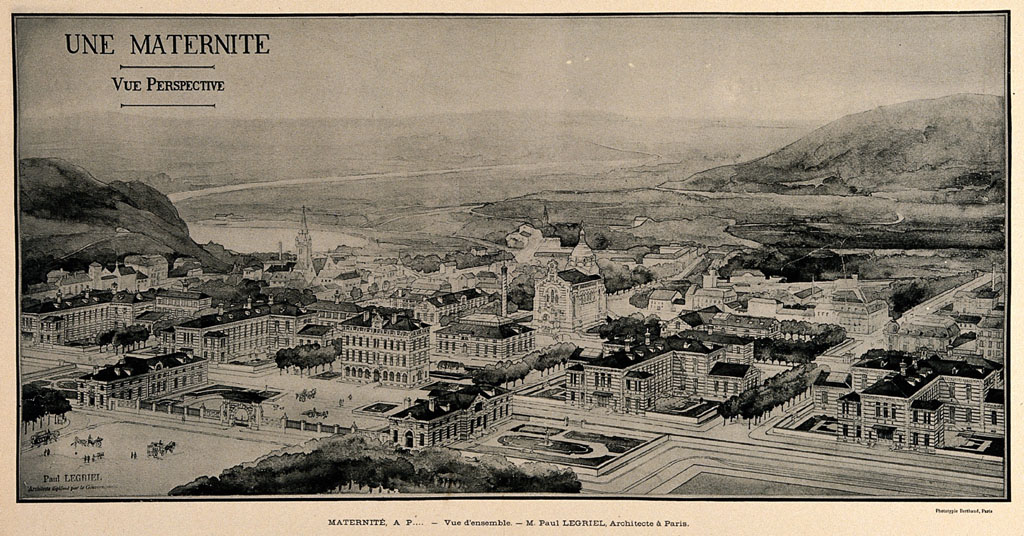

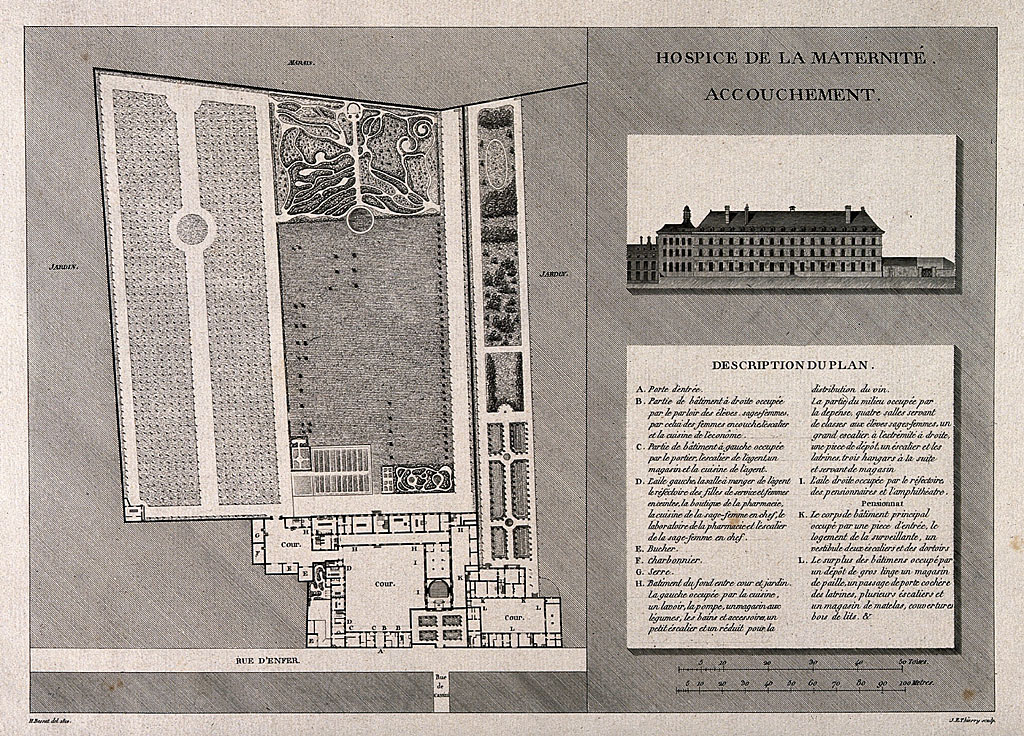

The Maternité de Paris, Port-Royal was the “lying-in” hospital for the poor women of Paris. The Port Royal abbey (Cistercian order, 1625) close to the Luxembourg Gardens, was transformed into a prison during the French Revolution (also called Prison de La Bourbe and Port-Libre). The Paris School of Midwives moved in 1794 from the Hotel Dieu (where it had been since 1610) to Port Royal. In 1814, the prison was converted into a maternity hospital, and was fully completed in 1818. In 1900, the Maternité had 283 beds for women in childbirth and 160 cradles. The cloister, chapel and the oratory where the Jesuits and Jansenists debated survive from the old abbey. Le Pautre built the chapel in 1646-1653.

The obstetrician Stéphane Tarnier pioneered use of incubators for premature infants at the Maternité at the end of the 19th century. He trained many other important French obstetricians, some of which (such as Auvard and Budin) went on to make important contributions to the care of newborns.

“It is impossible to describe the genesis of advanced newborn care without talking about the convent of Port Royal, a maternity and midwife school. At the end of the 19th century, new concepts of maternal and neonatal care emerged from the facility. Medical knowledge spread rapidly across Europe, and allowed the diffusion of new technology. Medicine entered a scientific era, which ultimately gave new directions to perinatal health care.

“The Port Royal convent, close to the Luxembourg Garden in Paris in 1625, was transformed into a prison during the French Revolution (also called Prison de La Bourbe and Port-Libre). In 1814, the prison was converted into a maternity, and was fully completed in 1818.

“The Paris School of Midwives moved in 1794 from the Hotel Dieu, close to the church of Notre Dame where it had been located since 1610, to two different specialized locations. One taught the art of delivery and was located at the Oratoire rue d’Enfer; the other, dedicated to post-partum and breastfeeding, moved to the ex-prison of La Bourbe. From there, it moved again to the Port Royal Maternity in 1814.” — “The Role of the French Midwives in Establishing the First Special Care Units for Sick Newborns,” by Paul L. Tobas and R. Nelson, Journal of Perinatology 22(1):75-77, January 2002.

A special pavilion for the care of newborn infants was established at the Maternité in 1893. It was opened and managed by “Madame Henry,” Dr. Tarnier’s Midwife-in-Chief, and had 12 incubators. Madame Henry resigned when Dr. Tarnier was succeeded by Dr. Pierre Budin in 1895.

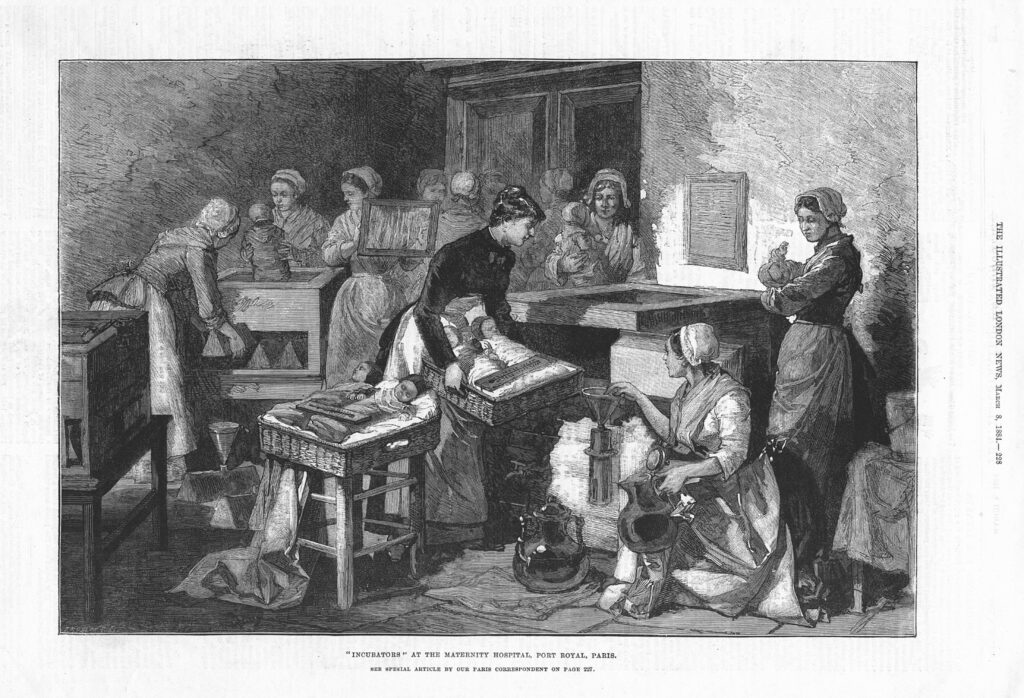

Above: Incubators at the Maternity Hospital, Port Royal, Paris (Maternité de Paris, Port-Royal). An engraving from the Illustrated London News, March 8, 1884, and attributed to Eugene Froment (1844-1900). Interestingly, the same engraving also appeared in the March 8, 1884 issue of Le Monde Illustré, Paris, but was there attributed to M. Claverie.

Elizabeth Blackwell, America’s first woman M.D., trained at the Maternité.

“Soon after graduation, Elizabeth left for England and Paris, hoping to supplement her Geneva education with study at the great hospitals of Europe. Though told that she would be welcomed at the teaching hospitals of Paris, the only opportunity she was offered was at the lying-in hospital, La Maternité. There she found that her medical training gave her no status above that of the uneducated French village girls who were training to become midwives. Nevertheless, she considered the training in women’s and children’s diseases, as well as midwifery, to be excellent.” — Elizabeth Blackwell, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine

Sadly, while at the Maternité, she examined the eye of a baby that had ophthalmia, was contaminated by this disease in her left eye and lost her sight. After visiting an eye specialist in Paris, her left eye was removed as well as her dreams of becoming a surgeon.

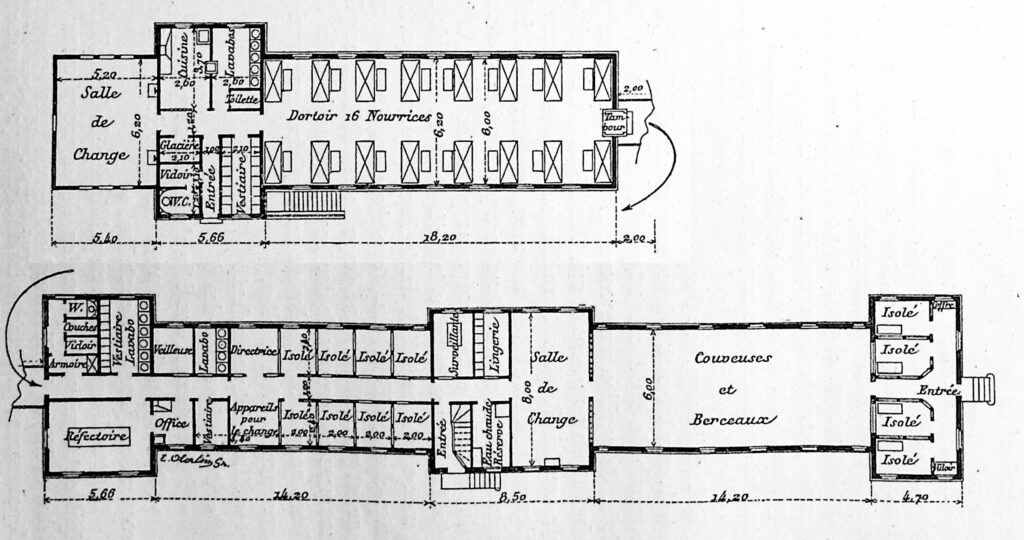

Above: The floor plan of the “weakling’s pavilion” at the Maternité, first established in 1893, and enlarged by Budin in 1897. The top section accommodated up to 16 wet nurses with their infants, dressing room, kitchen, washbasins and icebox. The bottom left section had eight isolation rooms for sick or potentially infected newborns, the nurses dining room, scales, bathtubs, breast pumps, and other equipment. The bottom right section had a large room for up to 16 healthy prematures in heated beds or closed incubators, four isolation chambers, and a room for bathing and dressing the babies. Source: Le Nourrisson, by P. Budin, Paris, 1900.

- Henry, Mme.: Fondation du pavilion des enfantes débiles à la Maternité de Paris [Foundation of the Pavilion of Sick Infants at the Maternity of Paris], Revue des Maladies de l’Enfance, Vol. 15, pp. 142-154, 1908. (French)

- Henry, M.: Fondation du pavilion des enfantes débiles à la Maternité de Paris [Foundation of the Pavilion of Sick Infants at the Maternity of Paris] , Revue des Maladies de l’Enfance, Vol. 15, pp. 142-154, 1908. (English translation)

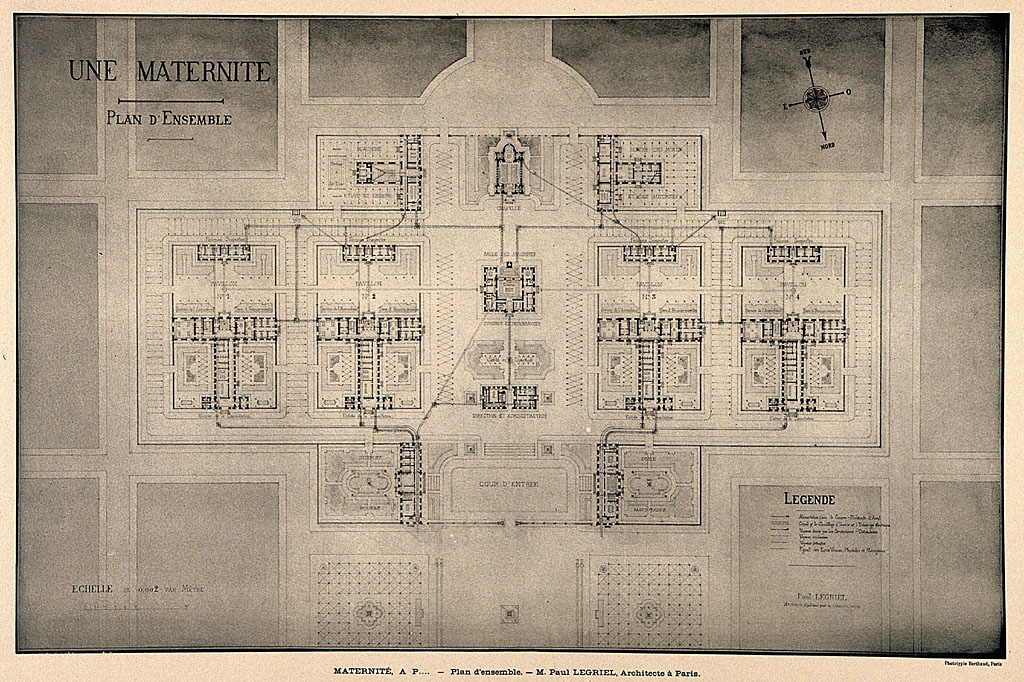

- Administration générale de l’Assistance publique à Paris, Hôpital de la Maternité, 1903. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / National Library of France.

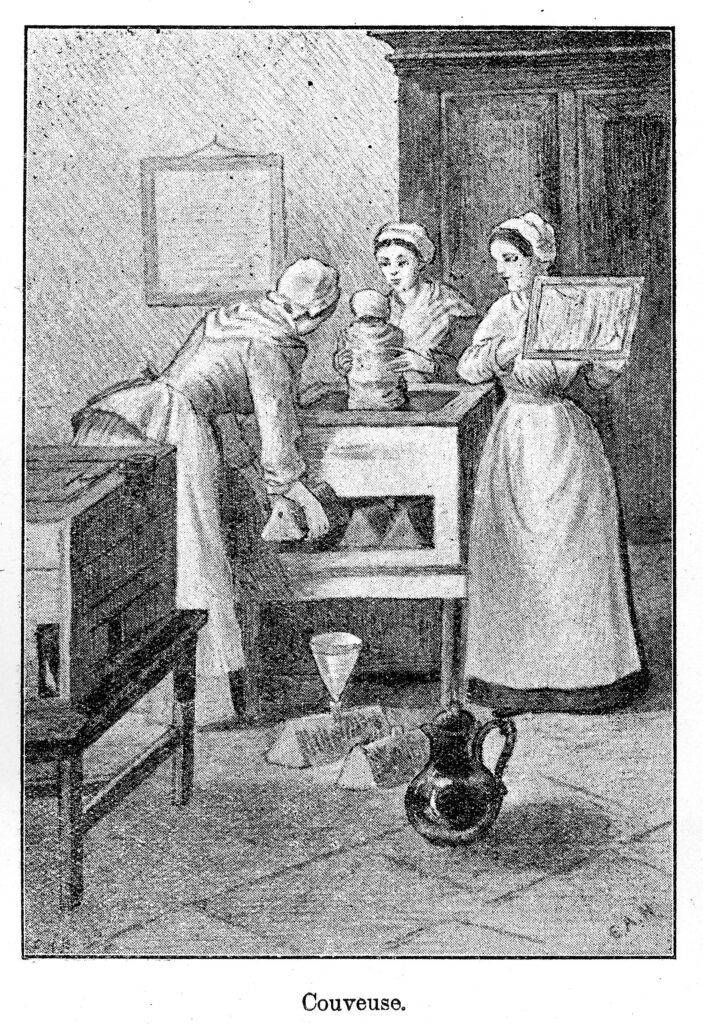

- Berthod, Paul: La Couveuse et le Gavage a la Maternité de Paris [The Incubator and Gavage Feeds at the Paris Maternity Hospital], 1887. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / National Library of France.

- Budin, Pierre: Service des Enfants Débiles a la Maternité, Année 1895-1897, 1896-1899. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / National Library of France.

- Budin, Pierre: Statistique de la Maternité de Paris, du 1er janvier 1895 au 28 février 1898, 1898. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / National Library of France.

- Editors, Maternal and Child Welfare, Pierre Budin and His Work, 1918.

- Editors, Occidental Medical Times, Mme. Henri’s Couveuse Department at the Paris Maternité, 1894

Last Updated on 12/26/23