Baby Incubators – James Walter Smith

Baby Incubators

By James Walter Smith

The Strand Magazine (London) 12:770-776, 1896

Click here to view a scan of the original article

“The little darlings!”

They were indeed darlings, and they were not cats, pugdogs, calves, or pigs, but babies — babies just big enough to put in your pocket, yet strong enough to emit a shrill wail that pierced through the glass doors of their metal houses, and compelled the nurses to hurry in hot haste. And when the nurses opened the glass doors to take the clean and chubby youngsters out, with blankets over their heads to keep the dear little things from catching cold, the nurses kissed and snuggled them as if they had been their very own.

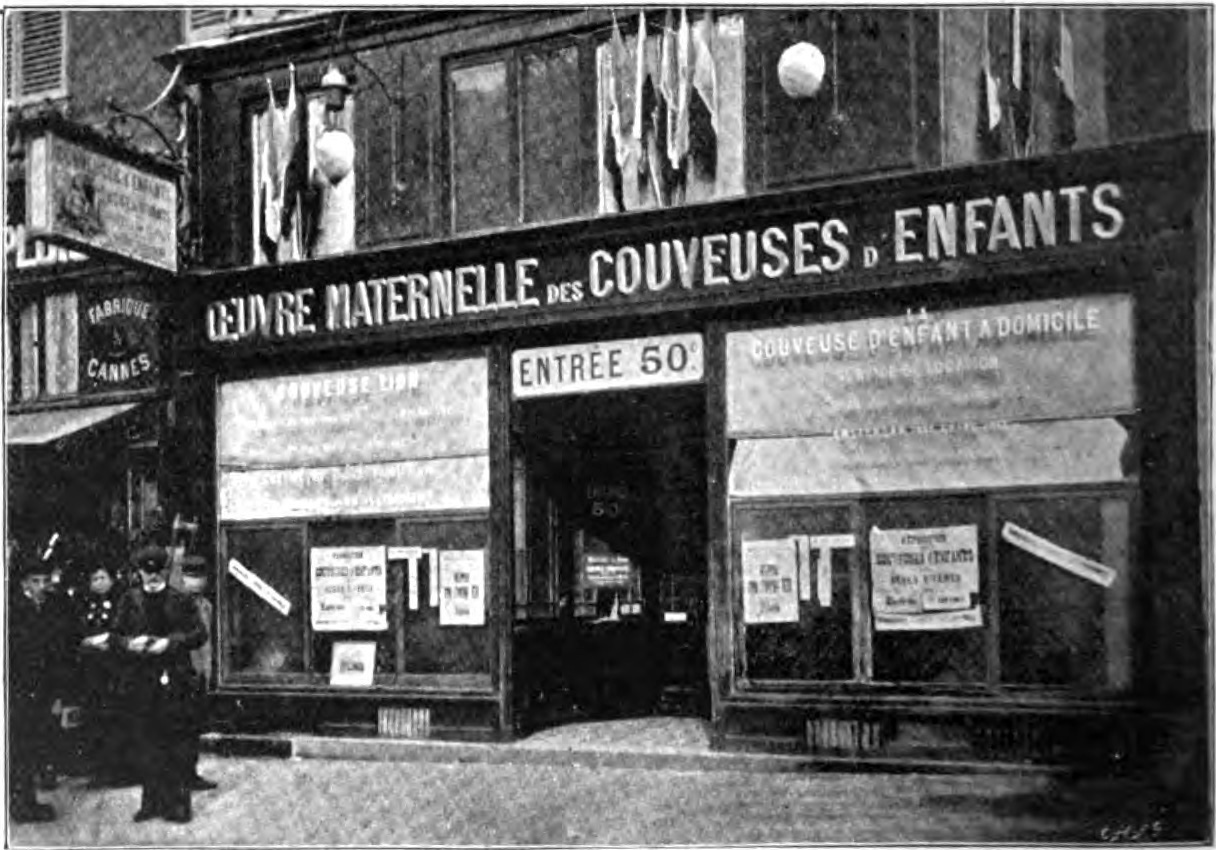

These rosy babies and their attentive nurses are to be found at 26, Boulevard Poissonière, Paris, one of the many establishments which a philanthropic physician, Dr. Alexandre Lion, of Nice, has created for the saving of infant life. The long French sign over the door, which stands out prominently in our photograph, may be roughly translated “The Baby Incubator Charity,” and the entrance-fee of fifty centimes, which visitors are asked to pay, goes for the support of the babes inside. Since the first of this year, over fifty thousand men and women have passed through the little door, and have marvelled, not only at the cleanness and domesticity of the place, but at the astonishing results of Dr. Lion’s work.

From the beginning of time there has been a legend that little babies are sent from Heaven. Unfortunately, however, some babies are sent before they are quite expected, and others, even though they are sent at the proper time, are too weak to fight the battle of life. In the words of the medical books, they are unable, in the early days of their existence, to resist the variations of atmospheric temperature. Frail and feeble, there is nothing left for the poor little tots to do except to die. That is to say, there was nothing — for it is these weakly children whom Dr. Lion has been keeping alive ever since he invented his “couveuse,” or incubator, in 1891.

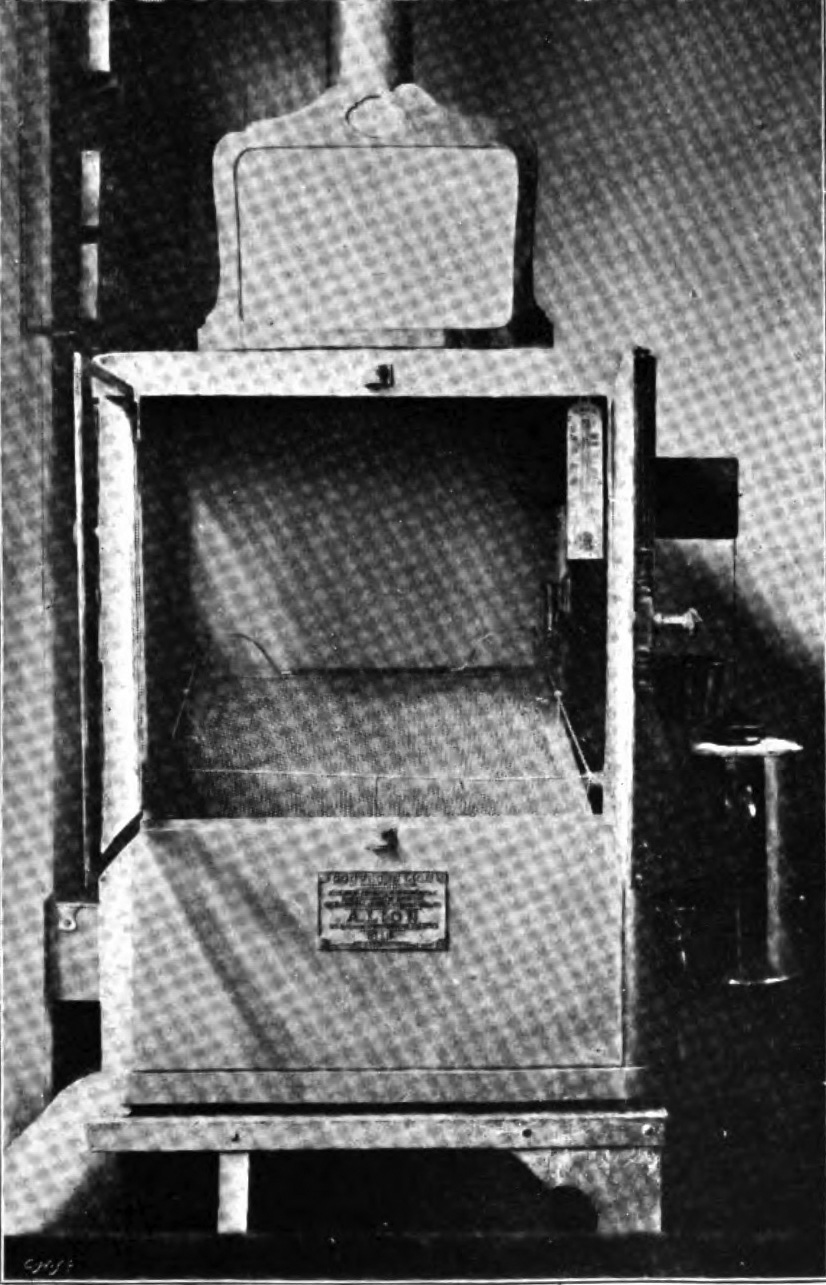

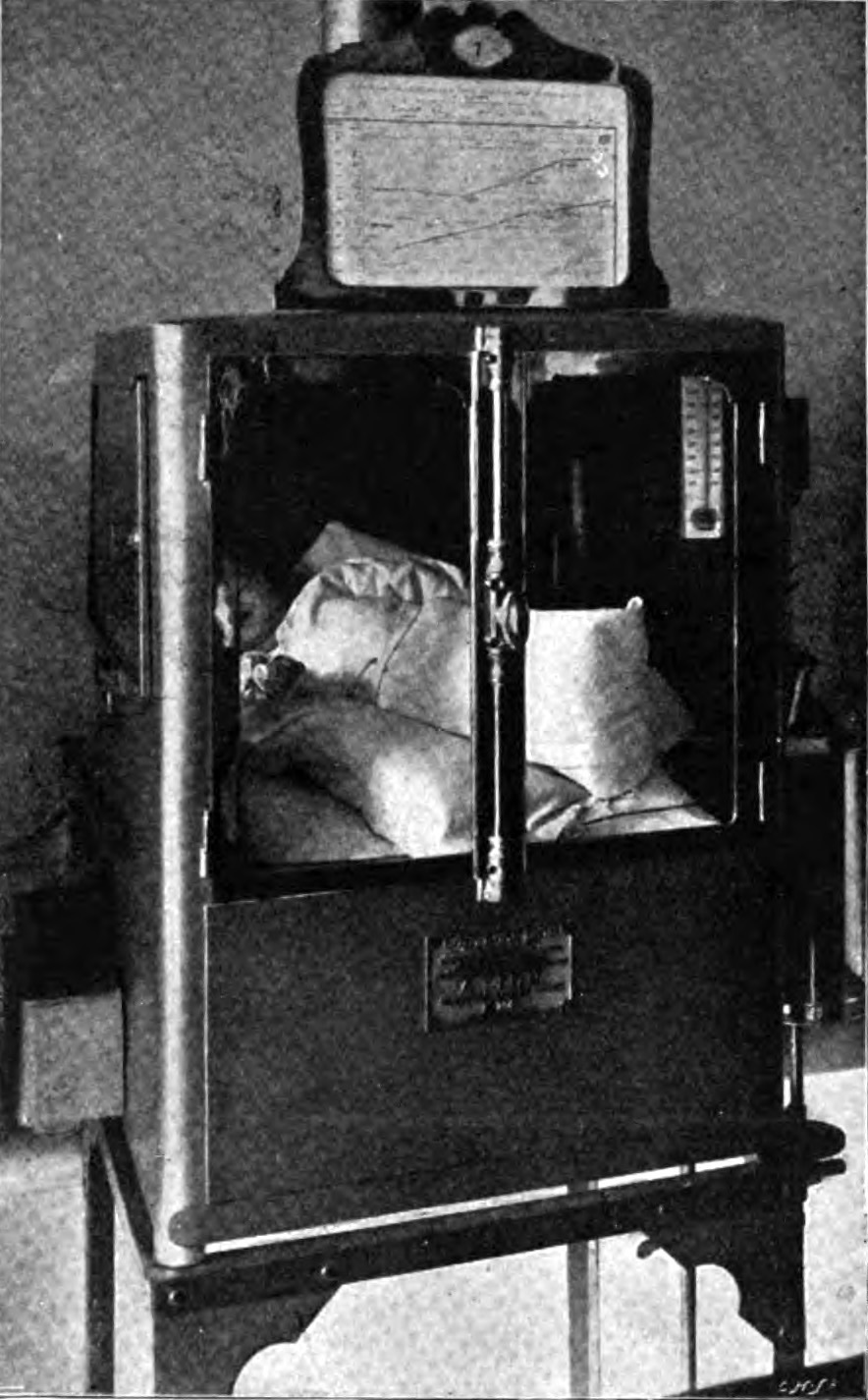

In the Paris establishment there are at least a dozen of these incubators, and each is occupied with a baby whose only aim in living seems to be to drink milk. A glance at the photograph reproduced at the top of this page will give an idea of the interior arrangement of the establishment, with its shining incubators placed against the wall in orderly row, its line of motherly-looking nurses ready to run upon the slightest cry to the bundle of animation inside, and the happy proprietor at the back. The picture of the incubator shows the inside and outside of a marvellously simple invention. It rests upon an iron stand; inside is a finely-woven wire spring suspended easily from the sides, upon which a mattress is placed for baby to lie on. Below the spring is a spiral pipe, through which a current of warm water continually runs. The water is heated by a lamp placed under the cylindrical boiler at the right-hand side, and the warm air circulates all around the baby, a thermometer in the corner showing the temperature. An ingenious apparatus regulates the temperature automatically, and augments or diminishes, according to special needs, the strength of the heat current.

“The ventilation,” says Dr. Lion, is afforded by a specially arranged pipe, which carries into the lower part of the incubator a jet of purified and filtered air. After its course through the couveuse, it goes out through the pipe at the top, and the little fan which you see indicates, by its rotation, the force of the air current.” In our photograph the fan is not shown, but it is placed at the summit of the pipe leading from the top of the couveuse. “It is necessary,” continued the Doctor, “that the air should be constantly circulating, and that the temperature inside the couveuse should be carefully regulated.”

While Dr. Lion was explaining that the incubator could be heated with gas, oil, electricity, methylated spirits, or any other fuel, he was interrupted by a most mournful wail from one of the incubators. “Healthy cry!” said the Doctor. “Wants something to eat.” And before the words were out of his mouth, the insignificant lump that had been disturbing the neighbourhood was hustled out of its hot-house into a glass-windowed apartment at the rear called the “Salle d’Allaitement,” or, in nice English, “baby’s dining-room.” As soon as the nurse was inside the dining-room, where scales, weights, bottles, mattresses, tables, and powder-boxes were arranged in orderly profusion, she took off the blanket that covered baby’s head, and by a series of quick movements and a most wonderful manipulation of the powder-puff, brought the youngster to a state of immaculate perfection. The baby didn’t like it one bit, although any man would have sworn the thing was done nicely. He kicked, cried, and executed gymnastics that would have made a professional blush; but he was conquered at last. This interesting operation — which, like the bearded lady at the circus, was “alone worth the price of admission” — took place on a padded table, and when it was over the baby got what it had been crying for. It was milk — pure, good, wholesome mother’s milk — and lots of it.

Every morning before breakfast, baby is weighed for the benefit of statistics. A new baby ought to weigh between six and seven pounds, but many reared by Dr. Lion have weighed much less. Pound babies rarely survive, even with the utmost care. The temperature of a normal baby is nearly always below 37 deg. Centigrade, and still lower the earlier the baby comes.

“And the incubator, by artificial means, increases the baby’s vitality, and stimulates the weak organs of his body?”

“Yes. But it is absolutely necessary that the baby should be placed in the couveuse immediately. Every minute that it is exposed to the variations of temperature its chances of life diminish. An early child rarely dies if it is exempt from hereditary disease and weighs not less than two pounds and three ounces.”

After this astonishing statement of fact, the Doctor put his hand on the top of the incubator and took down a curiously shaped spoon – a long bit of silver with a bowl terminating in a folded point. “When our little ones are too weak to swallow naturally, we feed them through the nose. The nurse places the milk in the spoon, puts it to the baby’s nose, and the baby breathes it in drop by drop. This method, however, is rarely necessary for more than two or three weeks. Sometimes we feed it by means of a tube, attached to the nurse, and placed in the baby’s mouth. In both cases, the baby is relieved of the labour of drawing in the milk, yet gets its healthful supply of food.”

Each baby is fed every two hours, and the number of squeals which I heard during the half-day that I spent with Dr. Lion and his rosy children showed me that babies, like bigger mortals, have an unerring idea of dinner-hours. The clever nurses had evidently hit upon the excellent plan of feeding the children at different times, in order that they might wake up in rotation. It would have upset the whole system if they had all squealed at once. Just as soon as they were fed, they were carried back to the incubators, with the inevitable blankets over their heads, and placed comfortably on the soft bedding, where they quickly sank to rest.

The use of the blanket is one evidence o the extreme care which Dr. Lion gives to his little charges. The temperature of the incubator is naturally higher than the temperature of the outside room, and, in the case of the premature babies, is maintained, at a degree approximate to the temperature of the baby at the end of six, seven, or eight months, as the case may be. The temperature of the “dining-room” is about 25 deg. Centigrade, or as near as possible to the temperature of the incubator as the nurses can stand. When our photographer went into the dining room to photograph the weighing of the baby, he stuck manfully to his labours, but came out with huge beads upon his brow. “Phew!” he cried, and Dr. Lion laughed, saying, “The nurses themselves have to get used to it.”

While the photograph was being taken, a bright-eyed, curly-headed child was running about the room, the picture of health and buoyant life. “This,” said the Doctor, lifting “la petite,” as he called her, to his shoulder, “is one of our prize babies. She is now four years and a half old, and she came into the world two months before she was expected. We put her in the incubator, and kept her there until she was nine months, and here she is now, a plump little chick that her mother wouldn’t part with for all the world.”

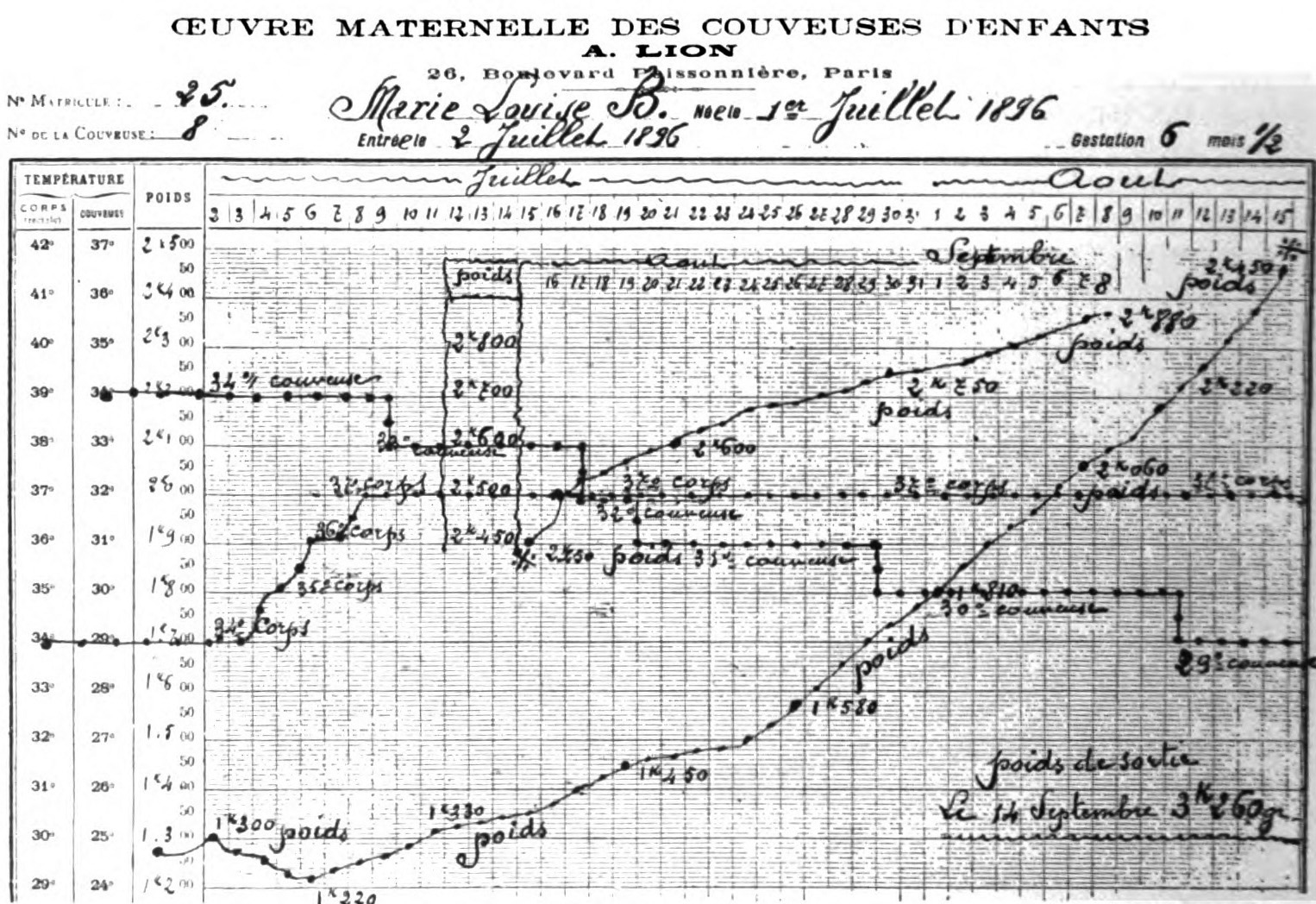

Above each incubator is a chart on which the temperature and weight of the babies are recorded each day, from the moment of their arrival to their departure. The card which we reproduce tells the story of a baby which made its appearance no less than two months and a half before it was looked for, and entered the incubator at once. The weight was slightly over two pounds, and the temperature of the body 34 deg. Centigrade. As may be seen form the dark and dotted line at the foot of the card, the baby fell slightly in weight for four days, when it suddenly took a turn for the better and rapidly increased until, at the middle of September, it had reached the weight of over seven pounds. The baby then left the establishment, having reached the weight of a normal child. The chart also shows the fluctuations in body temperature and the temperatures at which the incubator was kept on each day that the baby remained. At first, the card, with its French wording and weights, is a little confusing, but it is well worth study, as showing the success with which a seemingly doomed baby may be saved from death.

It is a fact that out of the 850,000 French children that come to the world each year, at least 130,000 perish quickly because they have come too soon. The “baby incubator” has already proved its ability to reduce this monstrous number of deaths. “The success of the system,” said Dr. Lion, “has been beyond my greatest hopes. At Nice, near where I was born, and where the charity was first started, I took 185 children in three years, and out of these, 137 were saved. This means that 72 per cent. of children who, in the natural course of things, have been spared to their mothers. A remarkable photograph of a group of babies reared at Nice in couveuses was taken in April, 1894. All the babies came before their time. Since last January, we have had sixty-two babies in the Paris couveuses, and of these eleven have died. Six of the eleven weighed less than two pounds, and their cases were almost hopeless. The others were brought in too late. They had caught a chill.”

“And why do you call your establishment a charity?”

“Because the incubators are placed at the disposal of the poor without cost. At Nice, the municipality has granted us money for the support of the establishment, and a large number of charitable ladies contribute money regularly. In Paris we depend upon the fee for admission to pay the nurses and other expenses. Each nurse gets sixty francs a month, with her lodging, clothes, and meals found, and each nurse takes care of three babies. The nurses remain for six months, and new nurses, whom I am constantly looking for and training, take the vacant places. Black women often take care of white babies, and white women take care of black babies, as occasion requires.”

The Doctor also said that people who could afford to pay for support of their little ones were charged a fixed sum, and that all children, irrespective of poverty or wealth, were under regular medical supervision. The incubators have also been placed in the Paris hospitals, and arrangements have been made for their introduction into homes where the mothers do not care to be separated from their babies. For the installation of the apparatus, in Paris, the cost is sixty francs a month. In London, the cost is about four pounds a month; but, as yet, few incubators have been sent to England.

At the present moment, the “Baby Incubator Pavilion” at the Berlin Exposition is the most attractive exhibit in the enormous building. In two months, over 100,000 people have visited it, more than 6,000 women having seen it in three days. The medical professors of Berlin are now collecting funds for the support of a permanent establishment in the German capital, similar to the one in Paris. There are already permanent “charities” in Bordeaux, Marseilles, Lyons, and Nice, and before next year has passed, Brussels and London will have establishments of their own.

Again we were interrupted by that long, shrill cry for milk. “It’s always the same,” said the Doctor. “No sooner do the youngsters get asleep than they dream of their food and wake up!”

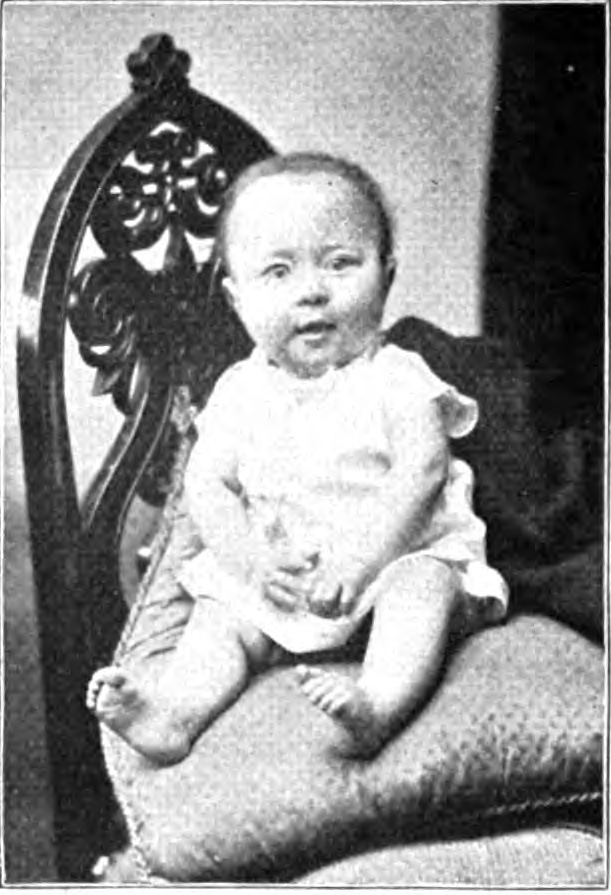

Again the dumpy infant was hurried to the dining-room, where the nurse tickled him with a feather, kissed him, and made him laugh. Then while he was laying bare and kicking on the table, the Doctor handed me three photographs, reproduced on this page. “Just look at the fat on that black baby,” he said.

Last Updated on 12/31/23