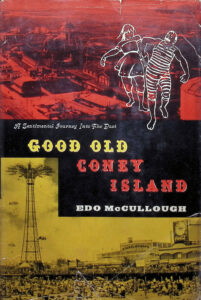

Good Old Coney Island

by Edo McCullough

Published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1957

Excerpt from pages 276-279

[The author relies Couney’s self-created legend, hence the history recounted here is not entirely factual.]

“You may talk, ladies and gentlemen, you may cough. They will not hear you. They do not even know you are here. And now, suppose you all follow me. Just come this way, if you will, and we will meet the fist of our temporary visitors.”

No sideshow in Coney’s history had as extended a run as the Premature Baby Incubators. At no other sideshow was the spiel so restrained, so lacking in boastful polysyllables, or so scientifically correct. The very fact that they were there at all was an anomaly, and one that many people were never able to re-solve. They could never have existed at all, and they most certainly would never have lasted-as they did-from 1903 to 1943, if it had not been for the unremitting scientific integrity of their founder, Dr. Martin Arthur Couney.

Dr. Couney was an Alsatian who came to Paris in the 1890’s to study under a celebrated pediatrician, and he early showed his special concern for premature babies, that is, those born at least three weeks before their normal forty-week term. In those days, medical men had no routine procedure for maintaining life in a premature baby; Dr. Couney assisted in the first fumbling efforts. A fair was to be held in Berlin, in 1896; most of the exhibits were to be medical and scientific; his chief urged Dr. Couney to conduct a demonstration of their methods at this fair. The exhibit was called the Kinderbrutanstalt, literally, the child hatchery, and it was a sensation. At the behest of an English promotor, Dr. Couney traveled the next year to Earl’s Court, but it is difficult to teach the English, their doctors refused to send premature babies to his Earl’s Court cradle, he was obliged to get his supply from Paris. The next year he was in Omaha, for the Trans-Mississippi Exposition; in 1900 he opened his incubators for the Paris World’s Fair; but in 1901 he was back in this country, at Buffalo, for the Pan-American Exposition. He decided to stay, for in those days it seemed that there was to be a World’s Fair or Exposition of some sort in some American city in each succeeding year; but in 1903 he was persuaded to come to Coney and exhibit his premature babies at Luna Park. With the exception of one two-year period, 1939-1940, when he was at the New York World’s Fair, he never left Coney save to retire, in 1943. During that time, of 8,500 premature babies, he saved 7,500, a record that could not be matched by the rest of organized medicine throughout the world. It is, indeed, difficult too highly to praise Dr. Couney’s efforts. At a time when, because of a combination of factors that included lack of interest, lack of specialized training, and lack of funds, the medical profession was skirting the problem of the premature baby, Dr. Couney’s incubators were almost alone in the country.

When first he arrived on Coney Island there was a flurry of indignation. The Brooklyn Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children inquired. Had he a medical license? What did he mean by exhibiting infants for a fee? Wasn’t there something vaguely improper about his procedures? The fact was that he had not had time to take out a practitioner’s license when he first arrived in this country, but that was soon remedied. As for the fees he collected (twenty-five cents at first; after 1937 this was reduced to twenty cents) they were manifestly necessary.

To care for premature infants costs a lot of money: for wet nurses, for trained nurses, both around the clock; for special formulae; for oxygen; and, as technology advanced, for air-conditioning and soundproofing and all the other perquisites of a modern hospital. To be sure, Dr. Couney made a living from his exhibits, but on the other hand he would have made far more had he chosen to close them down and go into private practice. In 1939, he reckoned his daily overhead at $140, which meant that he needed seven hundred customers on a daily average, to break even; in turn this meant that he had to do a land-office business on the weekends for, unlike the other sideshows, his incubators’ daily overhead was urgent and in-cessant. Nor was there anything even vaguely improper about his procedures. They were, indeed, the best in the country for his specialized work. American Medical Association spokesmen were always notably respectful when it came to discussing Dr. Couney’s methods and results.

The doctor was under no illusions as to the fact that he was running a sideshow, but he was nevertheless very careful to make his a very different sideshow. It was a scientific exhibit, and while he delighted in being fatherly to all the nurses and lecturers (never spielers or talkers) and others who staffed his enterprise he could be a very stern father when crossed. Rules were rules. Wet nurses were strictly forbidden to eat in local restaurants or to buy food from any of the perambulant peddlers. Lecturers were fired if they permitted jokes to creep into their spiel-oops, their scientific explanations. With the years, Coney came to be peppered with graduates of his incubators.

Two of them worked for a time at Luna Park; there was another in a local five-and-ten; a fourth, who was an electrician for a number of years at Steeplechase Park, used to come back so often to visit (on the house, professional courtesy) that at length he ended up married to one of the registered nurses.

And, the doctor noticed, many of his visitors came back again and again. They would identify with one or another baby and return regularly to see how it was doing. One Coney Island resident turned up once a week for thirty-seven seasons.

The smallest infant in Dr. Couney’s Coney Island experience weighed 705 grams, about one and one-half pounds. (The smallest survivor recorded in medical history weighed 600 grams, or about one and one-quarter pounds, but, as Dr.

Couney pointed out, in each of these cases the weight was measured some time after birth. A baby loses weight as soon as it has been born; it is doubtful that any baby weighing less than two pounds at birth could survive.) His own daughter Hildegarde was prematurely born and completed her term in his incubators, surviving to be a healthy young woman who became one of his principal assistants toward the end of his career.

“Now this little baby came in nine days ago. It weighed only one pound eleven ounces and we were afraid we might be too late. It was even bluer than that little fellow over there in the other incubator … Yes, maam, it was a premature birth … A little over six months . . .”

By the 1930’s, Dr. Couney’s were the only soft-spoken barkers left on Coney. The gentle, hypnotic art of Omar Sami was as dead as the dodo. No longer did the spieler call on psychological cunning; his only resource was racket….

Last Updated on 11/30/25