Étienne Stéphane Tarnier (1828-1897)

Stéphane Tarnier was a revered obstetrician and professor of the faculty of medicine in Paris who is also responsible for a key innovation in the care of premature infants. The son of a country doctor, he was born in Aiserey in eastern France on April 29, 1828, and grew up in Arc-sur-Tille, France, attending secondary school at he Lycée of Tijon. In 1845, he began his medical studies in in Paris, and finished around 1850. In 1856 he began working at the Maternité Port Royal in Paris. He presented his dissertation on puerperal fever, which demonstrated that puerpural fever was contagious, to the Académie de Medicine in Paris in 1857. The chief of the Maternité, Paul Dubois, was impressed with his work and made Tarnier chief of clinic at the hospital.

Tarnier adopted the asepsis techniques of Joseph Lister at the Maternité and also began the isolation of infected patients. As a result, maternal mortality at the Maternité dropped from 93/1000 deliveries to 23/1000 in the period 1870-1880, and then to 7/1000 in the next decade. Tarnier also focused on the care of premature infants, first implementing policies to keep the infants in hygienic isolation in a separate contained unit and at a warm temperature, and then implementing his first warming device (incubator) in 1881.

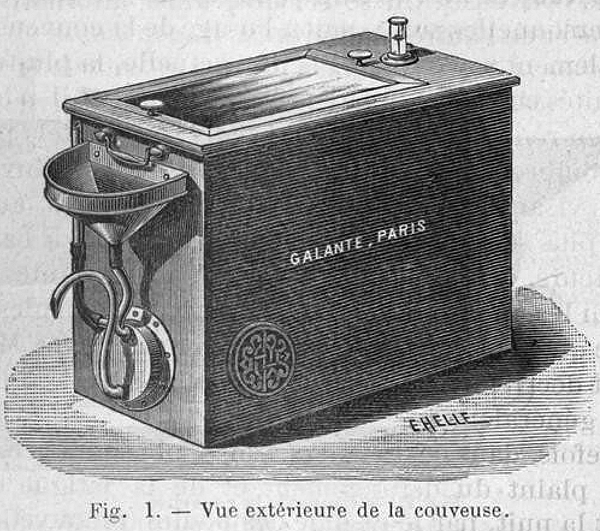

“In 1880 Tarnier had an infant incubator constructed similar to those used as chicken incubators. This incubator was built for him by Odile Martin, director of the Paris Zoo, and was built of such size that it could hold several children; and was installed in the Maternity Hospital of Paris in 1881. This is the first closed incubator which may be qualified as modern, for the perfected apparatus of our day differs from it only in detail.” — Julius Hess, Premature and Congenitally Diseased Infants, 1922.

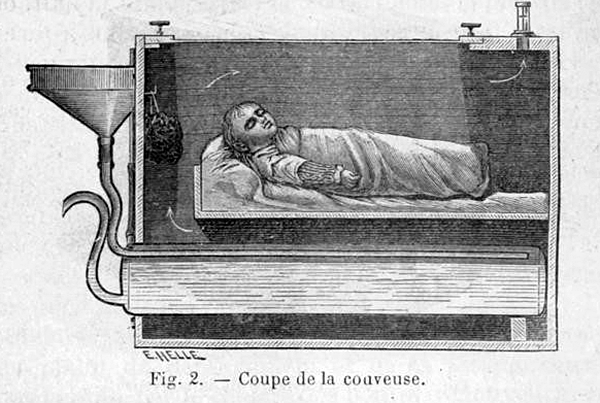

“Stéphane Tarnier developed his incubator model independently of Denucé and Credé. In 1880, Tarnier visited a bird exhibit at the Paris Zoo in Paris, France, where he later said he was inspired by an egg hatching incubator used by zoo director Odile Martin. Tarnier later asked Martin to build a modified incubator for him large enough to fit a human infant. That incubator could hold up to four infants at once and was made of a thick glass lid and wooden box frame with sawdust-insulated walls that could radiate heat and warm the infants. The incubator was placed upon a water tank heated with gas or alcohol that included a thermosiphon to separate fumes from the lower compartment of the box from the higher compartment that containing the infants. A thermosiphon circulates liquids and volatile gases for heating and cooling applications, such as heat pumps, or water heaters. In Tarnier’s design, air circulated from the bottom of the incubator through vents above the infant. Despite the thermosiphon, there was still a risk the incubator could fail or overheat and kill the infants inside.” — The Infant Incubator in Europe (1860-1890), The Embryo Project.

Subsequent versions of the incubator were for single infants and provided improved visibility for the infant, and those are shown in the engavings and other images that have come down to us. I have not been able to find any drawings or images of the original incubator that could hold multiple infants.

Above: This figure appears to show the earliest single-infant version of Tarnier’s incubator. Warm water was poured into the warming tank below the baby through the funnel from a vessel. Later versions of the incubator, created by Tarnier working with Auvard, Budin, and others, had a built-in heater with a thermostat for the water tank, while other versions used removable bottles of warm water in the lower compartment that could be slid in and out for replacement when they cooled.

“To lessen the risk of overheating, Pierre Budin, a student of Tarnier, modified the incubator by introducing a thermostat and a temperature sensitive alarm that would alert caregivers if there was a problem. Also, nurses placed a thermometer into the incubator to monitor temperatures without directly opening the box. In 1883, Tarnier’s student Pierre-Victor Auvard published a report in which he stated that Tarnier’s model reduced the infant mortality rate in half. Together with Auvard, Tarnier developed a model in response to the nurses in the maternity wards who had previously had to fill the water reservoir three times a day because they thought the thermosiphon seemed too risky to keep on for the whole day. The Auvard-Tarnier model was also a two-tiered sawdust insulated box, but instead of a tank it was heated with removable clay water bottles. Nurses could replace the water bottles with ease and did not have to frequently re-fill the device. At the time, this model was affordable, which encouraged hospitals to adopt it.

“The Tarnier-Auvard incubator model became increasingly popular device in maternity wards in Paris until the 1890s, and it spread to the US. In 1887, John Bartlett, a physician at the Chicago Policlinic, later renamed as the John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital, in Chicago, Illinois, replicated Tarniers incubator. Bartlett’s incubator differed from Tarnier’s original plan only slightly. Incubators designed during the late 1800s were mainly focused on keeping the infant isolated, clean, and warm. The early developers of incubators recognized the need to give premature infants a stable and sterile environment to provide the care they needed to survive.” — The Infant Incubator in Europe (1860-1890), The Embryo Project.

Tarnier made many important contributions to the art of obstetrics, including a better design for axis-traction forceps, the basotribe, and a method, of inducing labor using an intrauterine ballooon, along with important publications in the medical literature. He received many honors, and was named President of the Académie Nationale de Médicine in Paris in 1891.

Tarnier retired in 1897, publishing the results of his 40 years of research on puerperal fever in De L’asepsie et de L’antisepsie en Obstétrique (Asepsis and Antisepsis in Obstetrics). On the day of his retirement, he suffered a stroke, and died on November 22, 1897 at the age of 69.

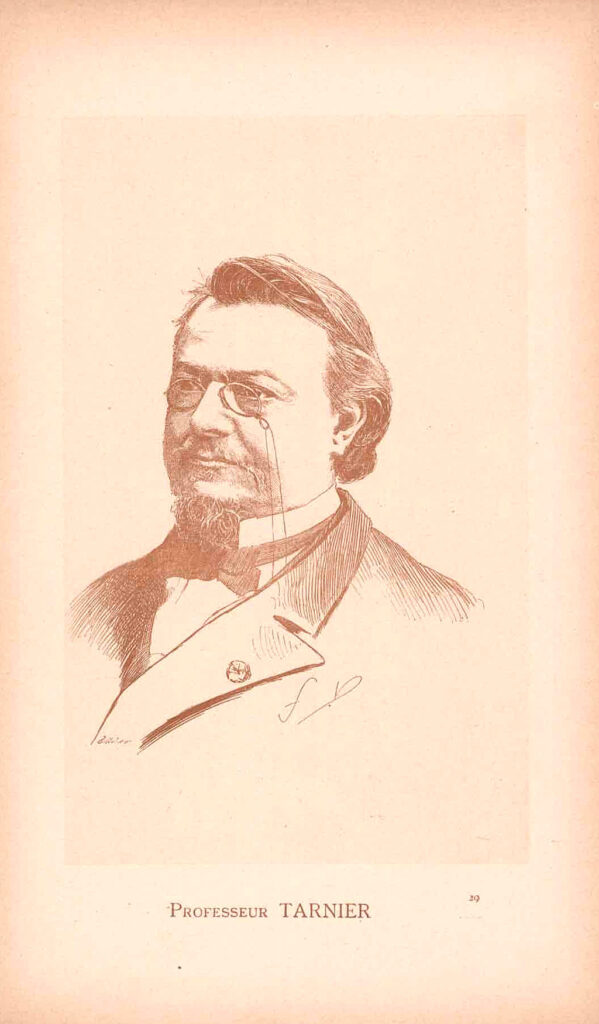

Above: Dr. Stéphane Tarnier. Photograph by Pierre Petit.

Above: Dr. Stéphane Tarnier. Tinted engraving of unknown origin.

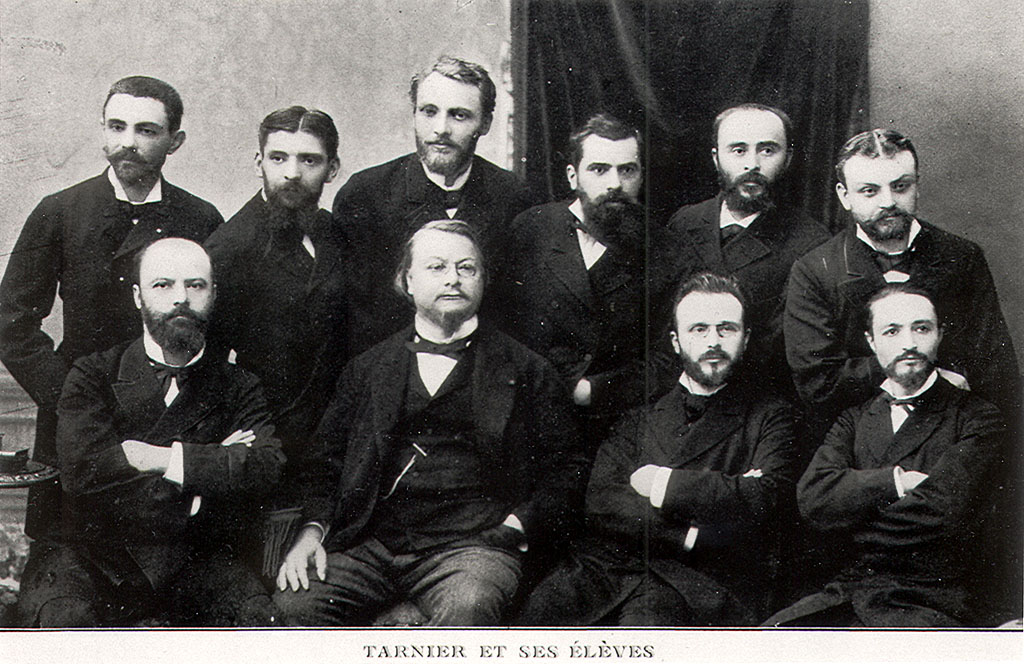

Above: Tarnier and his students and colleagues, including Budin. Back row, left to right: Auvard, Tarnier, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Bar, Maygrier, Pinard. Front row, left to right: Berthaut, Champetier de Ribes, Budin, Olivier.

Above: Dr. Tarnier’s obstetric forceps.

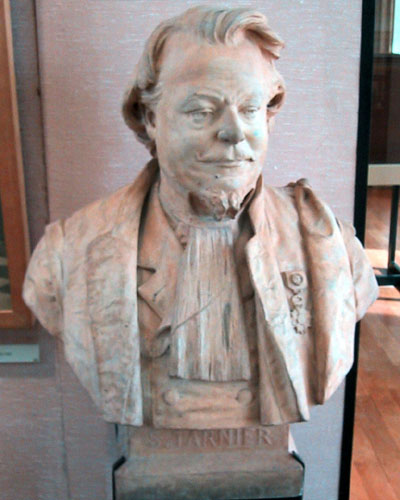

Above: a bust on exhibit at the Musée de l’Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, 47, quai de la Tournelle, 75005 Paris, France.

Above: A beautiful bas-relief marble monument to Professor Tarnier, erected in 1905, can be found at the intersection of Avenue de l’Observatoire and Rue d’Assas in the 6th arrondissement, Paris, France.

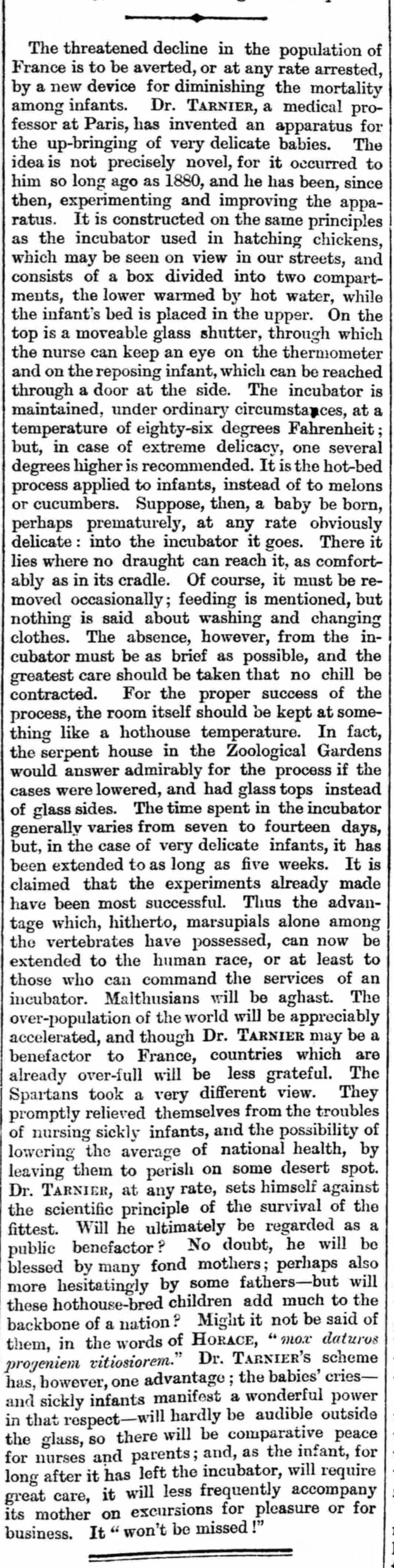

Press coverage in the UK in 1897:

- Tarnier Memorium with photos and obituary by M. A. Pinard of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris. Source: Wellcome Library.

- Stéphane Tarnier (1828–1897), the architect of perinatology in France, P M. Dunn, Archives of Diseases of Children, Fetal & Neonatal Edition

- Étienne Stéphane Tarnier, from Wikipedia

- Étienne Stéphane Tarnier (1828–1897), The Embryo Project

- The Infant Incubator in Europe (1860-1890), The Embryo Project.

- Maternité de Paris, Port-Royal

- Incubators at the Maternity Hospital, Port Royal, Paris. Source: Illustrated London News, 1884.

- De la Couveuse pour Enfants, Auvard, 1883.

- Incubators for Infants, London Illustrated News, 1884.

- Fondation du pavilion des enfantes débiles à la Maternité de Paris [Foundation of the Pavilion of Sick Infants at the Maternity of Paris], by Mme. Henry, Revue des Maladies de l’Enfance, 1908.

- “Stéphane Tarnier (1828-1897), the architect of perinatology in France,” by Peter M. Dunn, Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal & Neonatal Edition. 86(2):F137-9, 2002 Mar.

Last Updated on 04/05/23