Radiant Warmers

The history of the radiant warmer is a narrative of balancing the biological need for warmth with the clinical need for accessibility. It transformed from a failed glass-ceiling experiment into an indispensable tool of modern neonatal intensive care by mastering the science of “thermal neutrality.”

The journey began in 1963 with the work of Agate and Silverman,[1] who first reported the use of servocontrolled radiant heat in incubators. They demonstrated that heat could be emanated from an electroconductive glass plate built into the ceiling of an incubator.

Figures above are from the Agate-Silverman paper showing their several different technical approaches to radiant heating in a conventional Isolette incubator. Left: Nichrome wires are placed over the Lucite top. Center: Infra-red lamps mounted over a Pyrex plate which replaced the Lucite top. Right: Electrically conductive glass plate replaces the Lucite top.

While research proved that maintaining an infant’s abdominal skin temperature at 36°C significantly improved survival rates, the design was a commercial failure. The primary obstacle was a dramatic safety flaw: the electroconductive glass ceilings would occasionally shatter, making mass production impossible.

The logic behind these heating systems was solidified in 1966 by Silverman and associates.[2] They discovered that an infant’s oxygen consumption—and therefore their metabolic rate—was at its lowest when abdominal skin temperature was maintained between 36° and 37°C. This state, known as thermal neutrality, became the clinical gold standard. Consequently, the anterior abdominal wall was established as the “modality of choice” for routine thermometry, using a thermistor (sensor) to dictate the heat output of the warmer.

Early servocontrolled mechanisms were rudimentary “all-or-nothing” systems; they turned heat completely on or completely off. This created a volatile environment:

- The Apnea Risk: Researchers such as Paul Perlstein noted that wide temperature fluctuations (especially when incubator ports were opened) correlated with increased apneic episodes (prolonged pauses in breathing).

- Proportional Heat Control: To solve this, engineers moved away from binary switches to “proportional” control, which provided partial, steady heat to minimize fluctuations.

- The Computerized Frontier: Later, computer-assisted control was developed to maintain near-perfect stability. While a study of 210 infants by Paul Perlstein in Cincinnati demonstrated that these systems further reduced metabolic rates, the complexity of maintenance precluded them from becoming the industry standard.[3]

In 1969, Du and Oliver introduced the first practical open-bed radiant warmer for resuscitation of infants in the delivery room, the Merco Infant Warmer®. By placing heating elements 60 to 65 cm above the baby, they solved the “access” problem that had plagued enclosed incubators. In the high-stakes environment of the delivery room, the ability to resuscitate a baby without a plastic barrier was an overwhelming advantage. While these early models lacked safety alarms or servocontrols—considered unnecessary for short delivery room stays—they laid the groundwork for modern NICU beds.

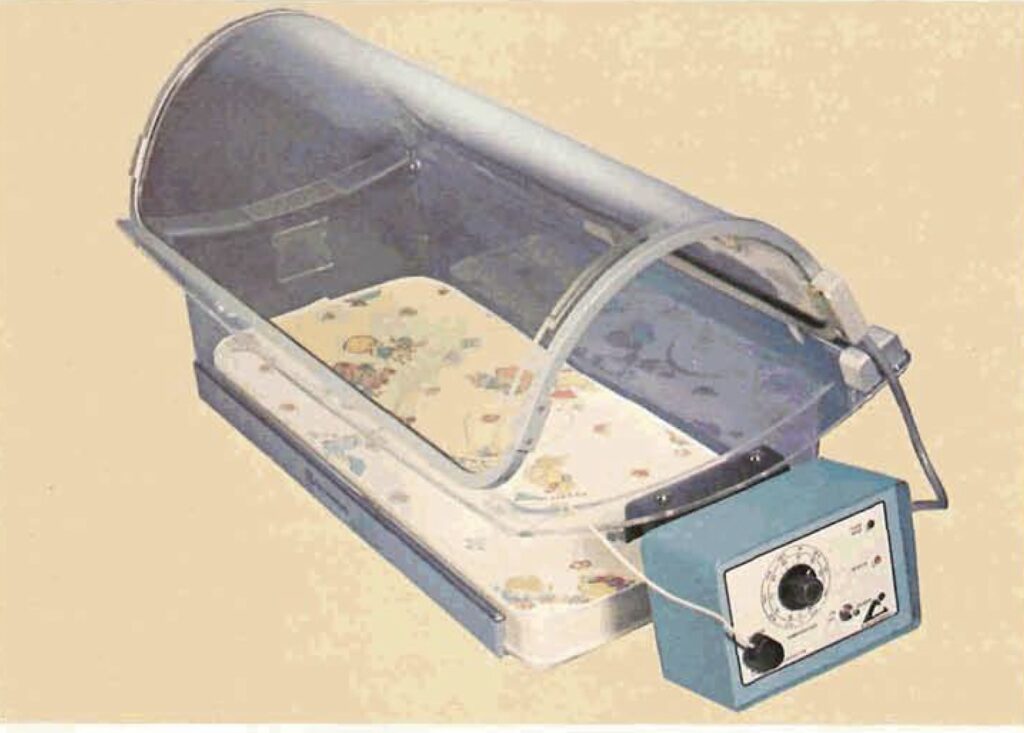

Around 1968, Sierracin (Cavitron) released the “Warming Cradle,” which had a heated overhead element. It was a spinoff from NASA technology developed for heated faceplates in test pilot pressure suits. The device was popular for a few years but was rapidly superseded by open bed radiant warmers as we know them today.

As neonatal care became more “intensive” and less “hands-off,” the radiant warmer moved from the delivery room to the permanent nursery. By 1972, both Air-Shields and Ohio Medical (Ohmeda) had released similar commercialized infant radiant warmer designs. These were highly successful, so much so that an American Academy of Pediatrics white paper on “Infant Radiant Warmers” in 1978 noted that 13,000 had already been sold in the preceding 10 years and warned of the risks and unknowns associated with their use.[4]

Early models were fairly minimalist, as shown in the examples below (Ohmeda on the left, AirShields on the right). These are sturdy devices and remain in widespread use today despite their lack of sophistication.

However, the open design of the radiant warmer has both advantages and disadvantages:

Advantages

- Immediate Access: Allows medical staff to perform procedures (intubation, umbilical lines, etc.) without losing heat or dealing with portholes.

- Rapid Rewarming: Highly effective at quickly raising the temperature of a hypothermic newborn.

- Visibility: Provides 360-degree observation of the infant, which is critical during resuscitation.

- Surgical Environment: Ideal for use during minor bedside surgeries where multiple clinicians need to surround the infant.

Disadvantages

- Insensible Water Loss (IWL): The open air and radiant heat significantly increase evaporative water loss through the skin, potentially leading to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

- Lack of Humidity Control: Unlike incubators, warmers cannot maintain a high-humidity environment, which is vital for extremely preterm infants.

- Environmental Sensitivity: Heater output can be affected by drafts, air conditioning, or people moving near the bed.

- Sensor Dependency: If the skin probe (thermistor) detaches, the machine may “think” the baby is cold and increase heat dangerously (risk of hyperthermia).

The concern over dehydration was so significant that the FDA was petitioned to disapprove radiant warmers. Critics argued that the transepidermal water loss in immature infants was a fatal flaw. The petition was ultimately denied. It was determined that the risks could be managed through clinical intervention rather than discarding the technology. Today, dehydration is avoided by:

- Adjusting Fluid Intake: Increasing water volume to offset evaporative loss.

- Heat Shields: Using specialized covers to reduce the vapor pressure gradient.

- Refined Servo Monitoring: Utilizing the abdominal thermistor to maintain the 36°C set point precisely.

Air-Shields and Ohio Medical/Ohmeda remain the dominant vendors of radiant warmers in the US, although both of them have been acquired or absorbed over time by larger conglomerates (Air-Shields by Hill-Rom and subsequently by Dräger Medical, and Ohio Medical/Ohmeda by GE Medical). Recent high-end models have gotten much fancier, with integrated monitors and lights and other devices or hybrid incubator designs (examples are the GE Ohmeda “Giraffe” bed on the left below and the GE “Omnibed” on the right).

In today’s NICUs, radiant warmers tend to be used in specific situations –

- During the admission of a small or unstable baby, to improve access for procedures such as intubation or line placement, or to warm the baby rapidly.

- When a baby becomes unstable or is in critical condition and constant immediate attention from several caregivers, and may need interventions such as intubation.

After a baby is stabilized, the baby will be moved to an incubator so it is less exposed to noise, drafts, excessive handling, etc.

For those who are interested in more technical details, I have included two patent documents from the mid-1990s for the major vendors of radiant warmers.

- Air-Shields Patent US5498229, filed September 9, 1994, granted March 12, 1996

- Hill-Rom Patent US5453077, filed December 17, 1993, granted September 26, 1995

[1] Agate, FJ and Silverman, WA: “The Control of Body Temperature in the Small Newborn Infant by Low Energy Infra-Red Radiation.” Pediatrics, May 1963, pages 725-733.

[2] Silverman, W. A., Sinclair, J. C., & Agate, F. J. (1966). The oxygen cost of minor changes in heat balance of small newborn infants. Acta Paediatrica, 55(3), 294–300.

[3] Atherton HD, Edwards NK, Perlstein PH, et al: A computerized incubator control system for newborn infants. In Computer Technology to Reach the People. New York, IEEE, 1975.

[4] Committee on Environmental Hazards: “Infant Radiant Warmers.” Pediatrics 51(1) 113-114, January 1978.

Last Updated on 02/16/26