Hess Incubator

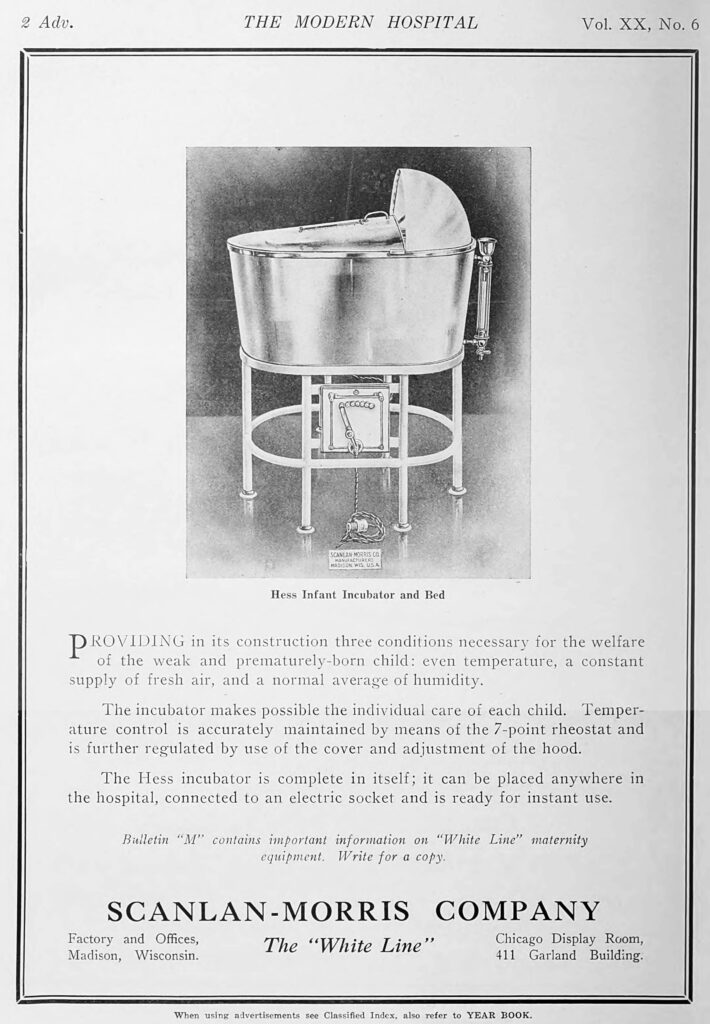

The Hess Incubator, specifically the Hess Infant Incubator and Bed, represents an important bridge between the early incubators of the 19th century and the sophisticated incubators found in the neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) of today. The incubator was developed around 1914–1915 by Dr. Julius Hess at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago. Hess was frustrated by the high mortality rates of premature infants and the limitations of the “Lion” style incubators, which were often seen as carnival attractions rather than clinical tools.

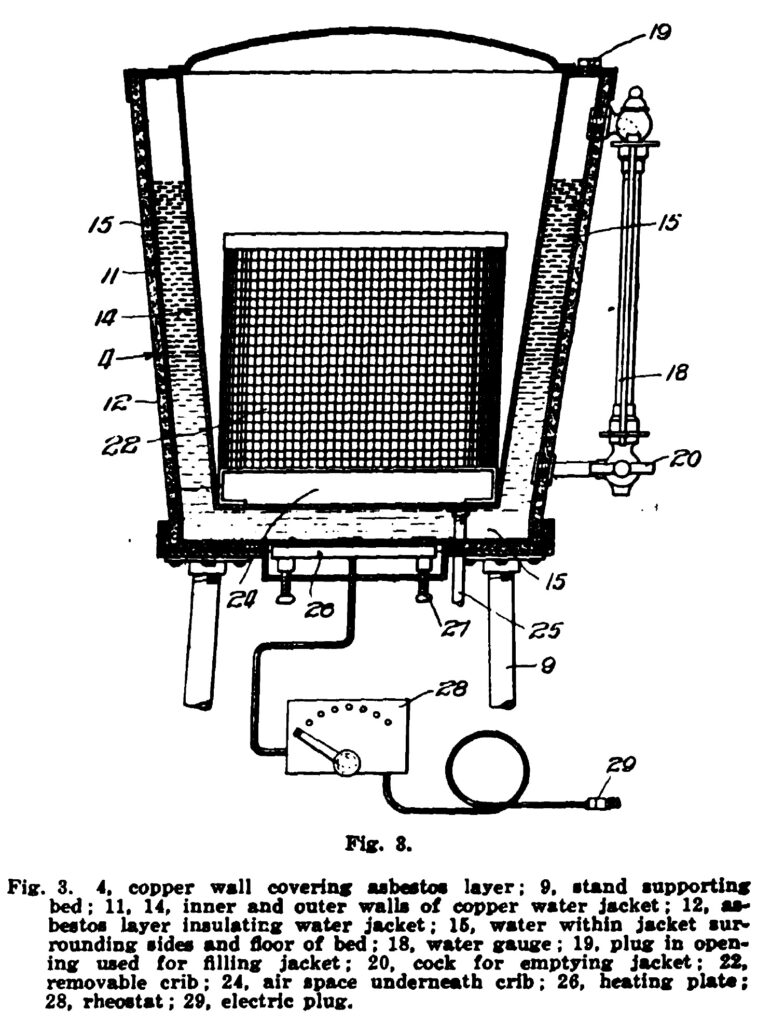

The initial design was essentially a water-jacketed metal tub. Hess focused on “indirect heat”—using a layer of warm water to surround the infant bed to ensure even, stable temperatures.

Dr. Hess described his invention thus:

“The bed shown in Figure 1 is constructed of heavy sheet copper with inside measurements as follows: length 30 inches, width 17 inches, and depth 13 inches. The floor and sides are surrounded by a water jacket 1 inch thick. The side walls, furthermore, are covered by a layer of cork one-fourth inch thick, which practically prevents heat radiation from the external surface, limiting heat radiation to the inner surface of the jacket, that is, sides and floor. On the left side a right angle hot water thermometer is inserted directly into the water chamber, which at all times registers the temperature of the water surrounding the bed. On the same side a water gage with faucet registers the height of the water and is also used for emptying the jacket during transportation. The jacket is filled through the inlet in the upper rim.

In the floor of the water jacket a one-quarter inch pipe is inserted to carry off any water which might flow into the bed in case of a leak, thus avoiding all danger of flooding the crib in event of an accident to the water jacket.

The bed proper rests on a standard (Fig. 2) 22 inches in height with a metal top surrounded by a metal rim 2 inches deep, and this is lined with asbestos. The standard is supplied with ball-bearing casters, allowing of easy transportation from one ward to another if desirable.

The electric heating apparatus (Fig. 2, Simplex Electric Heating Company) is so constructed as to operate on either direct or alternating current, and consists of:

1. A stove with a 6-inch surface specially constructed to carry a maximum capacity of 300 watts (ordinary 6-inch places have a capacity approximating 440 watts), which makes it impossible to heat the water above 155, at a room temperature of 75 F. This stove rests on a drop in the metal top of the standard, and can be raised or lowered by the four thumb screws seen in Figure 2, by which means the stove can be brought into direct contact with the floor of the water jacket. This is essential to the proper heating of the water and the prevention of overheating of the stove.

2. A rheostat fastened to the lower part of the standard (Fig. 2) with seven contacts: six of them are graduated to take current varying from 25 watts on Contact 1 to 300 watts on Contact 6. The seventh contact shuts off the current.” — Hess, JAMA, 1915.

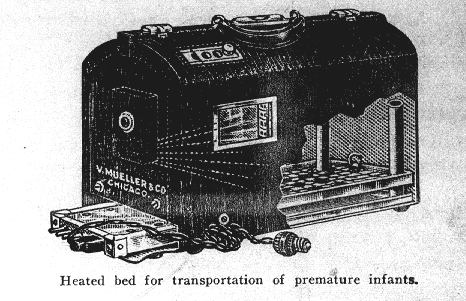

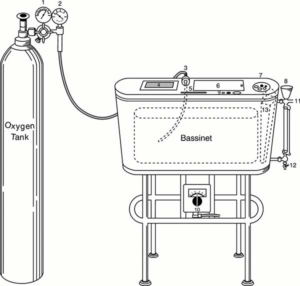

Around 1922, Hess refined the design into a portable “bed” that could be used for transport or stationary care. This version included a specialized oxygen hood, recognizing that premature infants often needed respiratory support as much as warmth.

By the mid-1930s, the Hess heated bed and incubator evolved to include integrated humidity controls and more precise electrical heating elements, moving away from manual water filling.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Stable Thermal Environment: The water-jacketed design provided exceptional heat retention and eliminated “hot spots.” | Access Issues: The early “tub” design required reaching over the top, which could be cumbersome for complex medical procedures. |

| Oxygen Integration: It was one of the first units to allow for a controlled oxygen-rich environment via a removable hood. | Risk of Infection: Maintaining the water jacket and humidity systems required rigorous cleaning to prevent bacterial growth. |

| Portability: The smaller Hess “beds” allowed for safer transport of infants within the hospital. | Weight: Due to the metal construction and water reservoir, the units were extremely heavy and difficult to move between floors. |

| Standardization: It moved neonatal care away from “intuition” and toward measurable, clinical standards. | Limited Visibility: Early models had smaller glass portals compared to the full-view plexiglass models developed later (like the Isolette). |

The Hess incubator was commercially manufactured and marketed by the Scanlan-Morris Company of Madison, Wisconsin. They worked closely with Dr. Hess to standardize the “Hess Infant Incubator and Bed,” selling it to hospitals across the United States. It was widely used (along with incubators of the Lion design, marketed in the US by the Kny-Scheerer Company) until the 1940s when the “Isolette” (a commercialized version of the “Chapple Incubator” manufactured by Air-Shields) introduced the use of transparent plastics and more advanced forced-air convection.

- Dr. Julius Hess

- An Electric-Heated Water-Jacketed Infant Incubator and Bed For Use in the Care of Premature and Poorly Nourished Infants, JAMA, 1915, by Julius Hess, MD.

- “New Equipment” from The Modern Hospital, Volume 6, 1916. A description of the Hess heated bed, with diagrams, by Julius Hess, M.D.

- Heated Bed for Transportation of Premature Infants, JAMA, 1923, by Julius Hess, MD.

- Oxygen Unit for Premature and Very Young Infants, AJDC, 1934, by Julius Hess, MD.

- Julius Hess’s incubator patent dated March 7, 1933.

- Julius Hess’s incubator patent dated November 7, 1933.

Last Updated on 02/17/26