Phototherapy

Phototherapy is a treatment for neonatal jaundice, which is typically caused by unconjugated (unprocessed) bilirubin. But what is bilirubin? Bilirubin is a breakdown product of hemoglobin that is released when old red blood cells are broken down. Normally, it travels to the liver to be processed by enzymes and excreted in the bile. Newborns often develop jaundice because they produce more bilirubin (they have more red blood cells with shorter lifespans), their livers are still immature and less efficient at processing it, and they reabsorb more from the intestine. Most newborn jaundice is temporary and harmless, but very high levels of unconjugated bilirubin can cross into the brain and cause serious injury (kernicterus) or death. Some medical conditions, such as a blood type incompatibility with the mother or various congenital anomalies of red cells or hemoglobin in the baby, can exacerbate the hyperbilirubinemia to extreme levels.

Prior to the widespread use of phototherapy, the only effective treatment for dangerous levels of hyperbilirubinemia was exchange transfusion, which is a specialized clinical procedure where a patient’s blood is gradually removed and replaced with donor blood or plasma, first performed by Alfred Hart in 1924.[5] The most common method, developed by Dr. Louis Diamond in 1946, utilizes the umbilical vein. A thin plastic catheter is inserted into the umbilical vein, and the procedure is performed in a series of cycles, removing a small volume of the baby’s blood (usually 5-20 mL) and replacing it with warmed donor blood until a “double-volume” of the baby’s blood is reached based on the baby’s weight, typically 160 mL/kg.

While exchange transfusion was a life-saving invention, it was a labor-intensive, time-consuming procedure in busy NICUs and had its own risks, among them the inadvertent transmission of infections via the donor blood. Phototherapy completely changed the therapeutic regime for hyperbilirubinemia, and (along with routine use of cord blood testing and RhoGam) made exchange transfusions a rare event – many pediatric residents and neonatology fellows in training today have never done one or even seen one performed.

The medical acceptance of phototherapy for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is a classic tale of serendipity evolving into rigorous science. The origins of phototherapy as a medical therapy trace back to Rochford General Hospital in Essex, England. In 1956, Sister Jean Ward, the nurse in charge of the premature unit, noticed that jaundiced infants improved when exposed to fresh air and sunlight. A pivotal “aha!” moment occurred when Sister Ward showed a baby to Dr. Richard Cremer, the consultant, during ward rounds; the infant was pale yellow except for a “strongly demarcated triangle of skin” that was much yellower. This yellow patch had been covered by a sheet, while the rest of the body was exposed to the sun. Later, a laboratory technician noted that a vial of blood left in the sunlight showed significantly lower bilirubin levels than expected. Dr. Cremer recalls:

One particularly fine summer’s day in 1956, during a ward round, Sister Ward diffidently showed us a premature baby, carefully undressed and with fully exposed abdomen. The infant was pale yellow except for a strongly demarcated triangle of skin very much yellower than the rest of the body. I asked her, ‘Sister, what did you paint it withiodine or flavine, and why?’ But she replied that she thought it must have been the sun. ‘What do you mean Sister? Sun tan takes days to develop after the erythema has faded.’ Sister Ward looked increasingly uncomfortable, and explained that she though it was a jaundiced baby, much darker where a corner of the sheet had covered the area. ‘It’s the rest of the body that seems to have faded.’ We left it at that, and as the infant did well and went home, fresh air treatment of prematurity continued.

A few weeks later and still during the warm summer months, blood from another deeply jaundiced infant was sent to the laboratory. After an unusual delay of some hours, and increasing anxiety, the plasma bilirubin was reported over the telephone to be 13-14 mg/100 ml. This was so clearly wrong that a fresh specimen was taken directly up to the laboratory, and an explanation requested both for the delay and for what seemed to be a very much lower level of bilirubin than expected in so jaundiced a baby. Mr. P. W. Perryman, the Biochemist, said he was sorry about the delay: ‘It should have been done before lunch: but I found the tube lying on the window sill and I did it myself, so I am sure it’s correct’. And he undertook to repeat the estimation on what was left of the morning specimen which was still lying, in full sunlight, on the window sill. When he had finished, he said the new specimen had gone up to 24 mg/100 ml, but that he couldn’t understand how it was that the old specimen seemed to be lower than ever and now read only 9 instead of 14 mg/100 ml as reported in the morning; at last the light dawned. [6]

Dr. Cremer and his colleagues investigated these observations, proving that it was visible blue light, rather than heat or UV rays, that caused the breakdown of bilirubin. In 1958, Cremer published the first formal study in The Lancet, documenting how artificial light lowered bilirubin in nine premature infants.[1] Despite the results, the American medical community largely ignored the findings for a decade, skeptical of the small sample size and wary of “unscientific” light-based treatments.

The breakthrough in US acceptance came through the work of Dr. Jerold Lucey at the University of Vermont. In 1968, Lucey, along with Mario Ferreiro and Jean Hewitt, published a large-scale randomized controlled trial involving 111 premature infants.[2] The study provided irrefutable statistical evidence that phototherapy was effective and safe, leading to its widespread adoption in the U.S. by the mid-1970s, and the release of practice guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2004 and 2022.[4] It is now the standard of practice world-wide, using “blue” or “blue-green” light with wavelengths of 460-490 nm. (It is not ultraviolet light.)

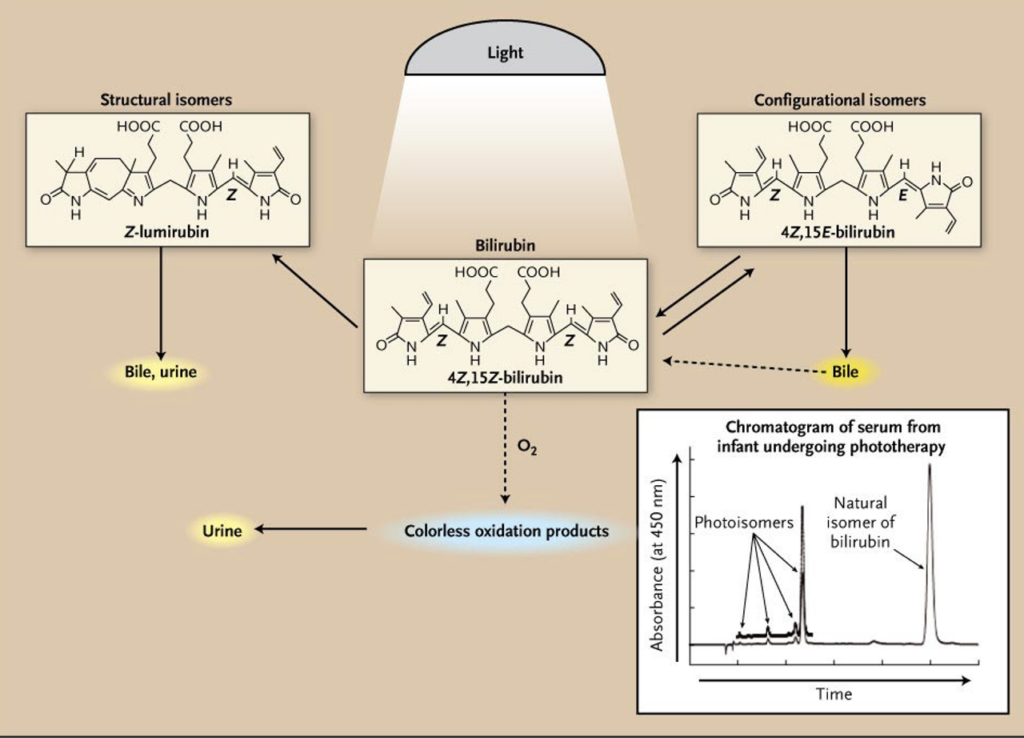

Although phototherapy had been demonstrated to be effective, it took longer for the mechanism of action to be understood. Initially, it was thought that bilirubin was being degraded by a process of photo-oxidation. While photo-oxidation of bilirubin does occur, it is now known to be a very slow process and not a significant contributor to the decline in bilirubin levels. In 1985, Antony McDonagh and colleagues identified a specific chemical process involved — structural isomerization — where light converts bilirubin into to two different isomers that (unlike naturally occurring bilirubin) do not require processing by liver enzymes before being efficiently excreted in the bile and urine.[3]

Mechanism of Phototherapy

Timeline of Key Contributions

| Date | Contributor | Milestone |

| 1956 | Sister Jean Ward | Observed that sunlight reduced jaundice in premature babies. |

| 1958 | Dr. Richard Cremer | Published the first evidence of artificial light’s efficacy in The Lancet. |

| 1968 | Dr. Jerold Lucey | Conducted the first major U.S. randomized trial, confirming safety/efficacy. |

| 1970s | Pediatric Community | Phototherapy becomes the standard of care, replacing exchange transfusions. |

| 1985 | Dr. Antony McDonagh | Identifies the primary chemical mechanism (photoisomerization) |

| 2004/22 | AAP Guidelines | American Academy of Pediatrics formalizes clinical thresholds for light therapy. |

Further reading on jaundice and kernicterus:

- Pioneers in the Scientific Study of Neonatal Jaundice and Kernicterus

by Thor Willy Ruud Hansen, MD, PhD, from Pediatrics 106(2):e15, August, 2000.

by Thor Willy Ruud Hansen, MD, PhD, from Pediatrics 106(2):e15, August, 2000. - The Rhesus Factor and Disease Prevention, a Witness Seminar held at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, on 3 June 2003. Posted here by permission.

- Neonatal Jaundice, A Selected Retrospective, by Lawrence M. Gartner

[1] Cremer RJ, Perryman PW, Richards DH: “Influence of Light on the Hyperbilirubinemia of Infants,” The Lancet, 271 pp. 1094-1097, May 24, 1958.

[2] Luce J, Ferreiro M, Hewitt J: “Prevention of Hyperbilirubinemia of Prematurity by Phototherapy,” Pediatrics 41(6) pp. 1047-1054, June 1968.

[3] McDonagh AF, Lightner DA: “Like a Shrivelled Blood Orange — Bilirubin, Jaundice, and Phototherapy,” Pediatrics 75(3) pp. 443-455, March 1985.

[4] Kemper AR et al: Clinical Practice Guideline Revision: Management of Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant 35 or More Weeks of Gestation. Pediatrics August 2022; 150 (3): e2022058859. 10.1542/peds.2022-058859

[5] Dunn PM: “Dr. Alfred Hart (1888-1954) of Toronto and Exsanguination Transfusion of the Newborn,” Archives of Disease in Childhood 1993; 69: 95-96.

[6] Dobbs RH, Cremer RJ: “Phototherapy,” Archives of Disease in Childhood, 50:833, 1975.

Last Updated on 02/19/26