Tarnier-Auvard-Budin Incubator

The history of the infant incubator is a pivotal chapter in neonatal medicine, involving the translation of agrarian technology to life-saving medical equipment. The evolution of the Tarnier-Auvard-Budin models represents the first successful attempt to industrialize the care of premature infants.

The modern incubator originated in late 19th-century Paris. In 1878 (some sources cite 1880), Stéphane Tarnier, a prominent obstetrician at the Maternité de Paris, visited the Jardin d’Acclimatation (the Paris Zoo) in the Bois du Boulogne. He was struck by the efficiency of the warming chambers used to hatch poultry. Recognizing that premature infants, like chicks, succumbed primarily to hypothermia, he envisioned a similar “human hatchery.”

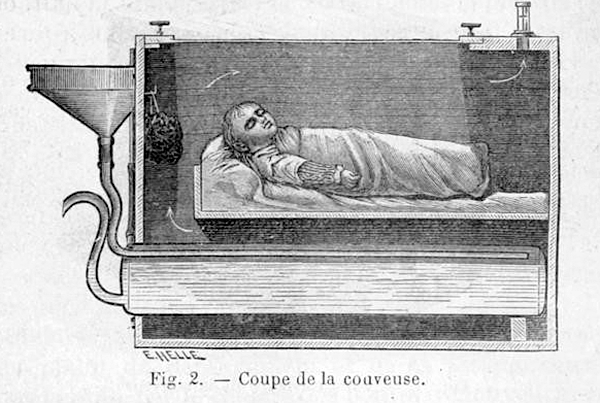

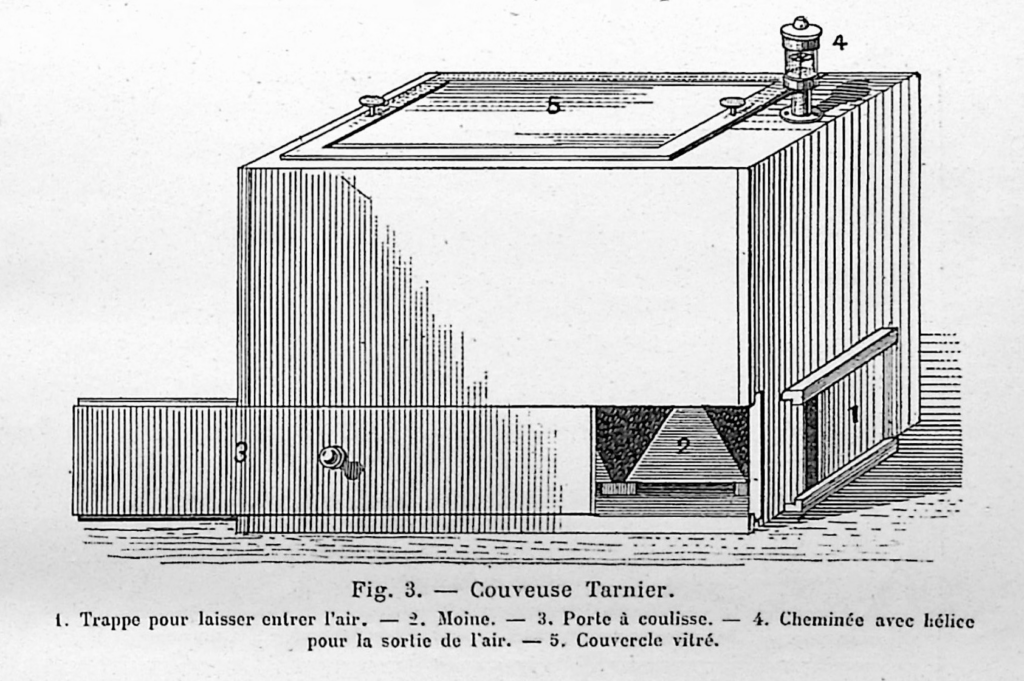

Tarnier collaborated with Odile Martin, the zoo’s poultry manager and engineer, to adapt the design. The first “Tarnier-Martin” incubator was introduced at the Paris Maternité in 1881. It was a large, wooden, two-tiered box capable of holding several infants, heated by a water tank and a gas-powered thermosiphon.

Tarnier conducted the first clinical trials, famously demonstrating that mortality for infants under 2,000 grams dropped from 66% to 38% within just a few years of its implementation.

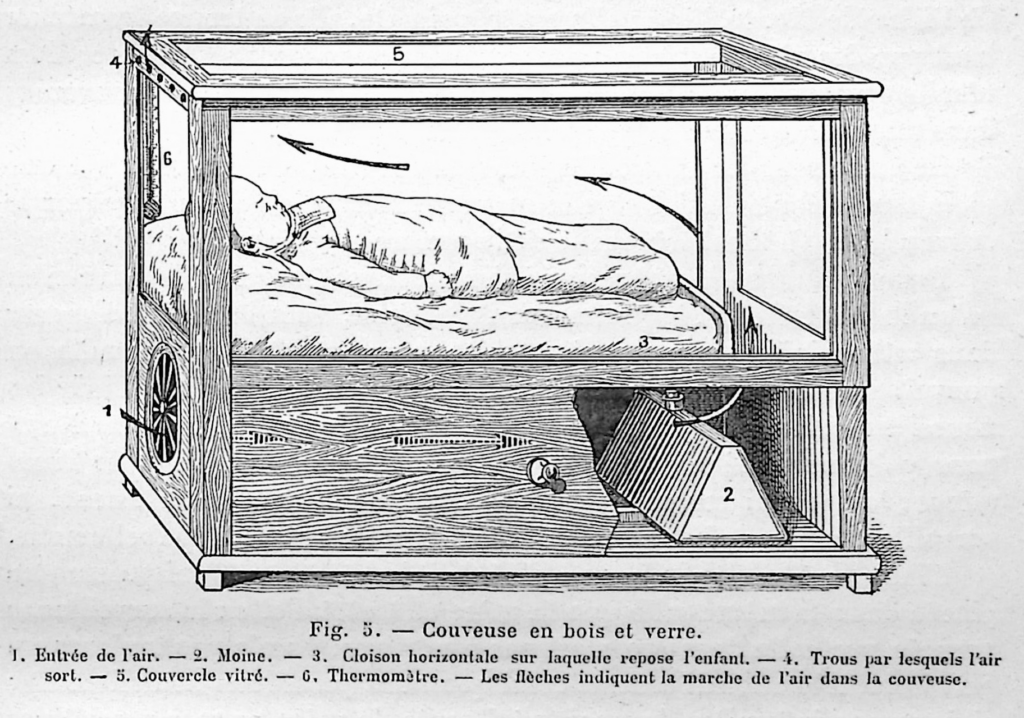

1883, Pierre-Victor-Adolphe Auvard, a student of Tarnier, published a significant modification. The original thermosiphon was expensive and difficult for nurses to maintain. Auvard replaced the complex heater with removable clay hot-water bottles (brocs) placed in a bottom compartment. This “Tarnier-Auvard” model was cheaper, portable, and easier to clean.

Pierre Budin was Tarnier’s successor. He further refined the incubator by adding glass sides for better observation of the infant (to detect cyanotic attacks) and introducing the Reynard regulator, an early thermostat that activated an electric bell to warn nurses if the temperature rose too high.

The various iterations of the Tarnier-Auvard-Budin incubator had advantages and drawbacks.

| Advantages | Drawbacks |

| Thermoregulation: Provided a stable, warm environment that prevented lethal heat loss. | Hygiene Issues: The wooden frames and sawdust insulation were porous and difficult to disinfect, harboring bacteria. |

| Observation: The glass lid (and later glass walls) allowed nurses to monitor breathing without exposing the baby to cold air. | Manual Labor: In the later versions, nurses had to replace hot water bottles every few hours, leading to temperature fluctuations if they were busy. |

| Infection Control: Isolated the infant from the crowded, often septic hospital wards. | Fire Risk: The Tarnier-Martin early gas-heated models posed a fire hazard in hospital settings. |

| Inexpensive: Could be built by local carpenters or small-scale instrument makers using Auvard’s published diagrams. | |

| Portable: The Auvard and Budin models required no plumbing or gas lines, making it suitable for any ward or even a private home. | |

| Open-Source: Tarnier, Auvard, and Budin did not patent their designs for personal profit. Odile Martin did patent his inventions, but apparently never commercialized or enforced the patents. |

While Tarnier, Auvard, and Budin apparently made no effort to commercialize their design, they published widely, and adaptations of their incubator were widely used throughout Europe because of their simplicity and can be found in pictures from various hospitals throughout the early 1900s (see our “Incubators Through the Years” page). At least a few companies are known to have produced commercial versions that were based on the Tarnier-Auvard-Budin design, such as the the glass and metal incubator advertised in a Paris medical supplies catalog seen below, and the “Hearson Thermostatic Nurse” manufactured in London.

At the same time as Tarnier, Auvard, and Budin were refining and using their incubator, the “Lion Incubator” invented by Alexandre Lion in the 1880s, was being widely used in maternity hospitals, institutions, and expositions. Budin knew of its existence, but considered it too complex and too expensive for use in the Paris Maternité Other designs emerged in the early 1900s, such as the “Rotch Incubator,” “Hess Incubator” and the “Chapple Incubator.” After World War II, the Air-Shields Isolette based on the Chapple design found rapid adoption and quickly supplanted all other designs.

Primary Sources (French)

- Auvard, P. V. A. (1883). “De la couveuse pour enfants.” Archives de Tocologie, Vol. 14, pp. 577–609.

- Berthod, Paul (1887): La Couveuse et le Gavage a la Maternité de Paris

- Budin, P. (1900). Le Nourrisson: Allaitement et Hygiène — Enfants Débiles et Enfants Nés à Terme. Paris: Octave Doin.

- Eustache, G.. (1885): “Une Nouvelle Couveuse pour Enfants Nouveau-Nés,” Journal des Sciences Médicales de Lille.

- Tarnier, S. (1885). “Couveuse pour enfants.” Bulletin de l’Académie de Médecine, 2nd Series, Vol. 14, p. 116.

Primary Sources (English)

- Budin, P. (1907). The Nursling: The Feeding and Hygiene of Premature and Full-term Infants. Translated by W. J. Maloney. London: Caxton Publishing. (The authorized English translation of Budin’s masterwork).

- Sadler, S. H. (1896). Infant Feeding by Artificial Means: A Scientific and Practical Treatise on the Dietetics of Infancy. London: Scientific Press. (Contains detailed contemporary descriptions of the Tarnier-Auvard incubator).

Patents (French)

- Odile Martin Patent 136015, Filed April 9, 1880, “Artificial incubator with continuous egg rotation, with its pressure motor regulated by the water flow.”

- Odile Martin Patent 141161, Filed February 15, 1881, “A device system called an artificial mother, for raising premature infants.”

Last Updated on 02/17/26